Figure Collections for Each Part of the FEST Log

To gain a quick familiarity with the layout of the arguments in the FEST Log, we have provided here a comic book style summary of all the figures in Parts 1 through 4

Part 1: Initial Explorations (Part 1 has no figures)

Part 2: Inspiration from the History of Physics

Part 2: Inspiration From The History Of Physics

#006: In Search of a Theory

#007: Unanticipated Discoveries in Science

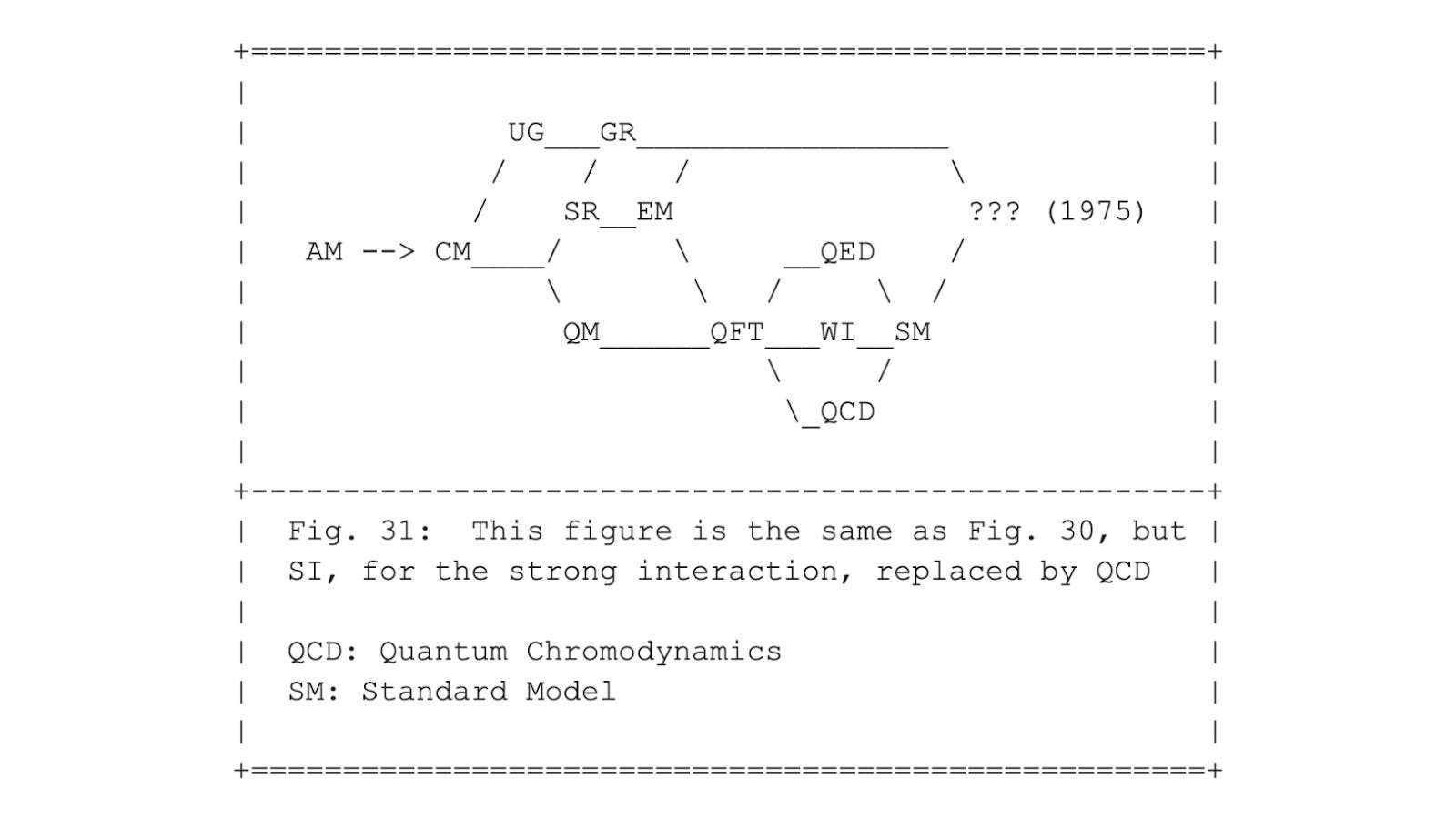

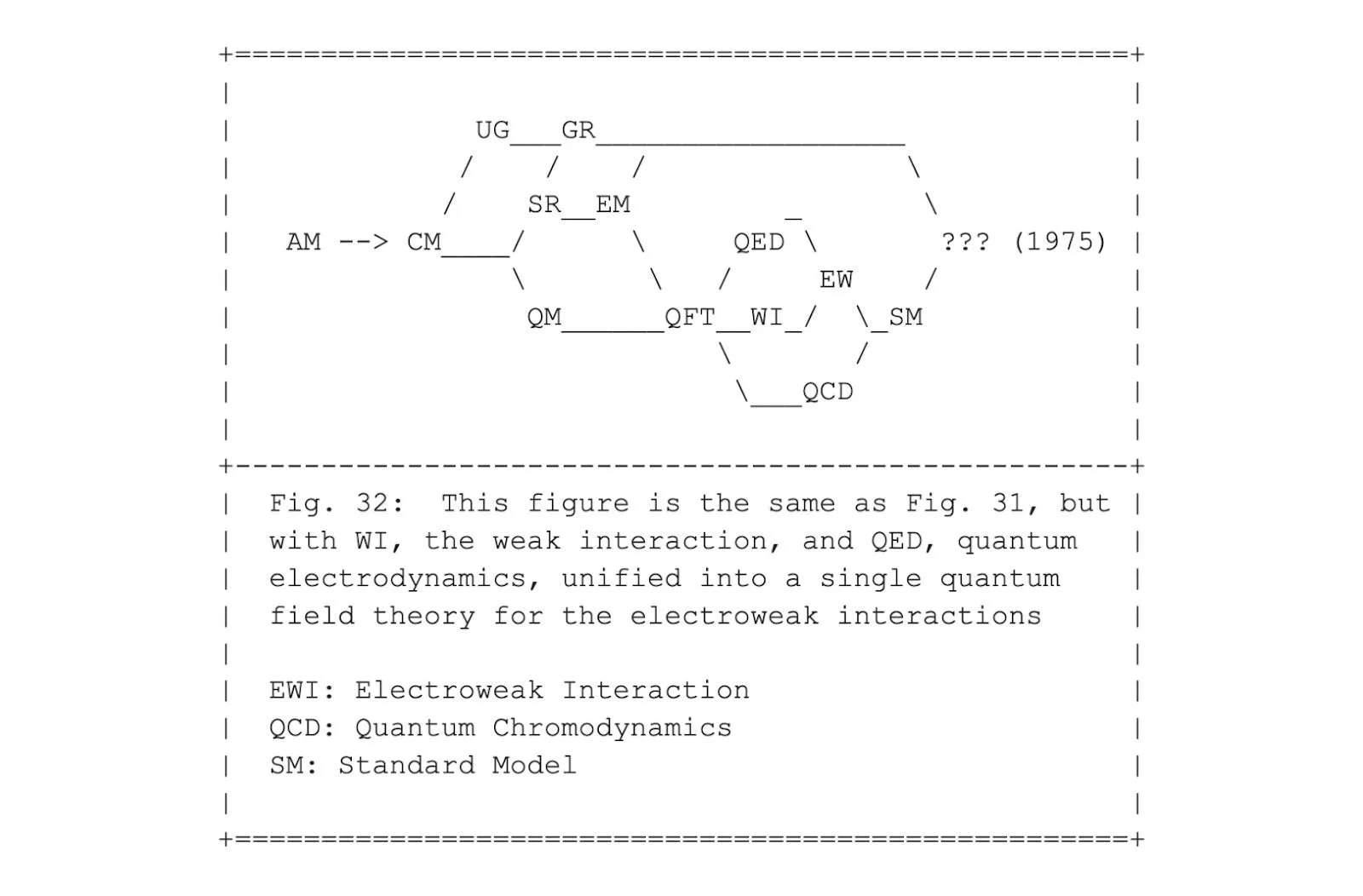

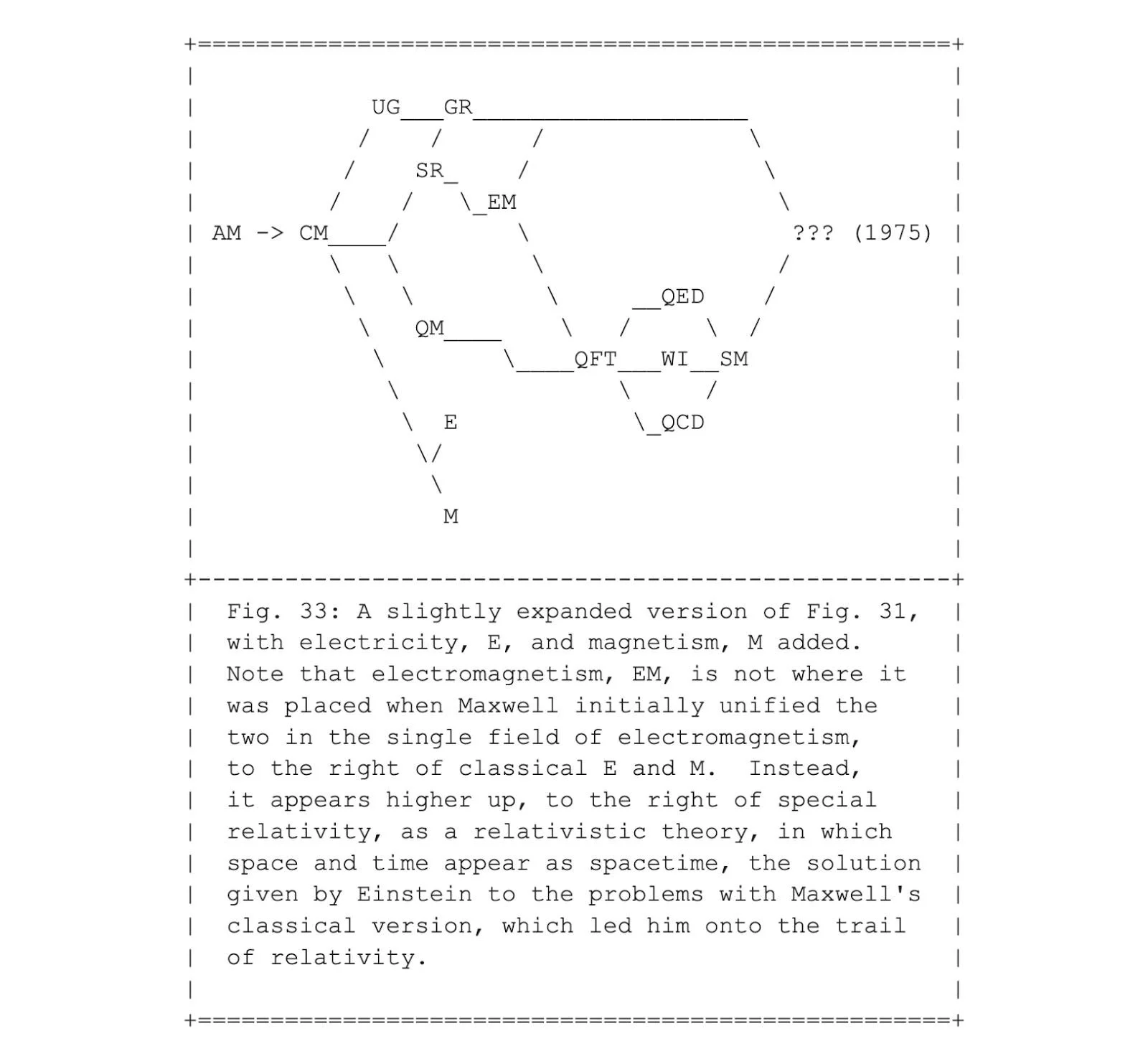

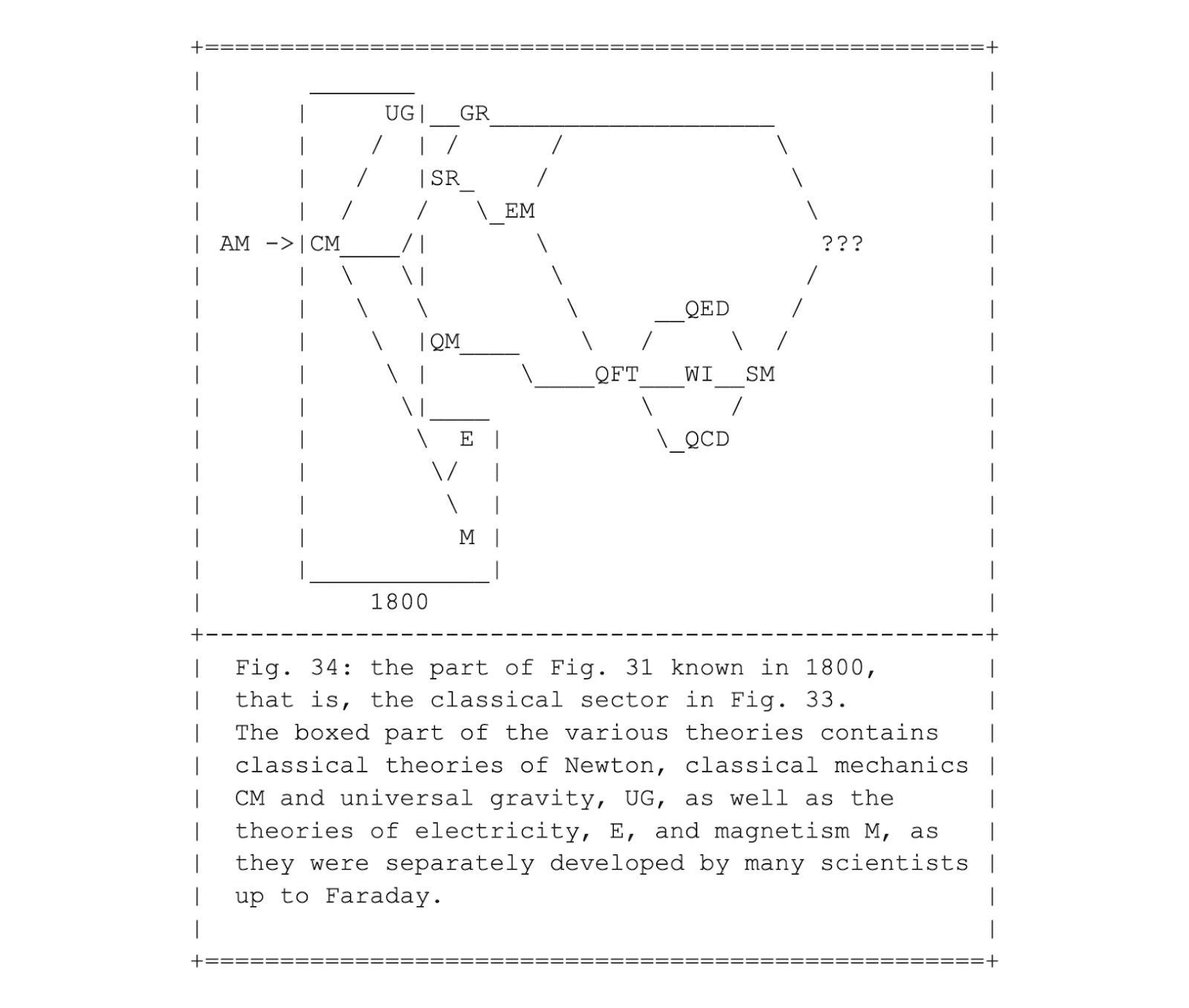

#008: A Picture Book of Physics Theories

#009: From Maxwell to Einstein

#010:The State of Physics in 1925

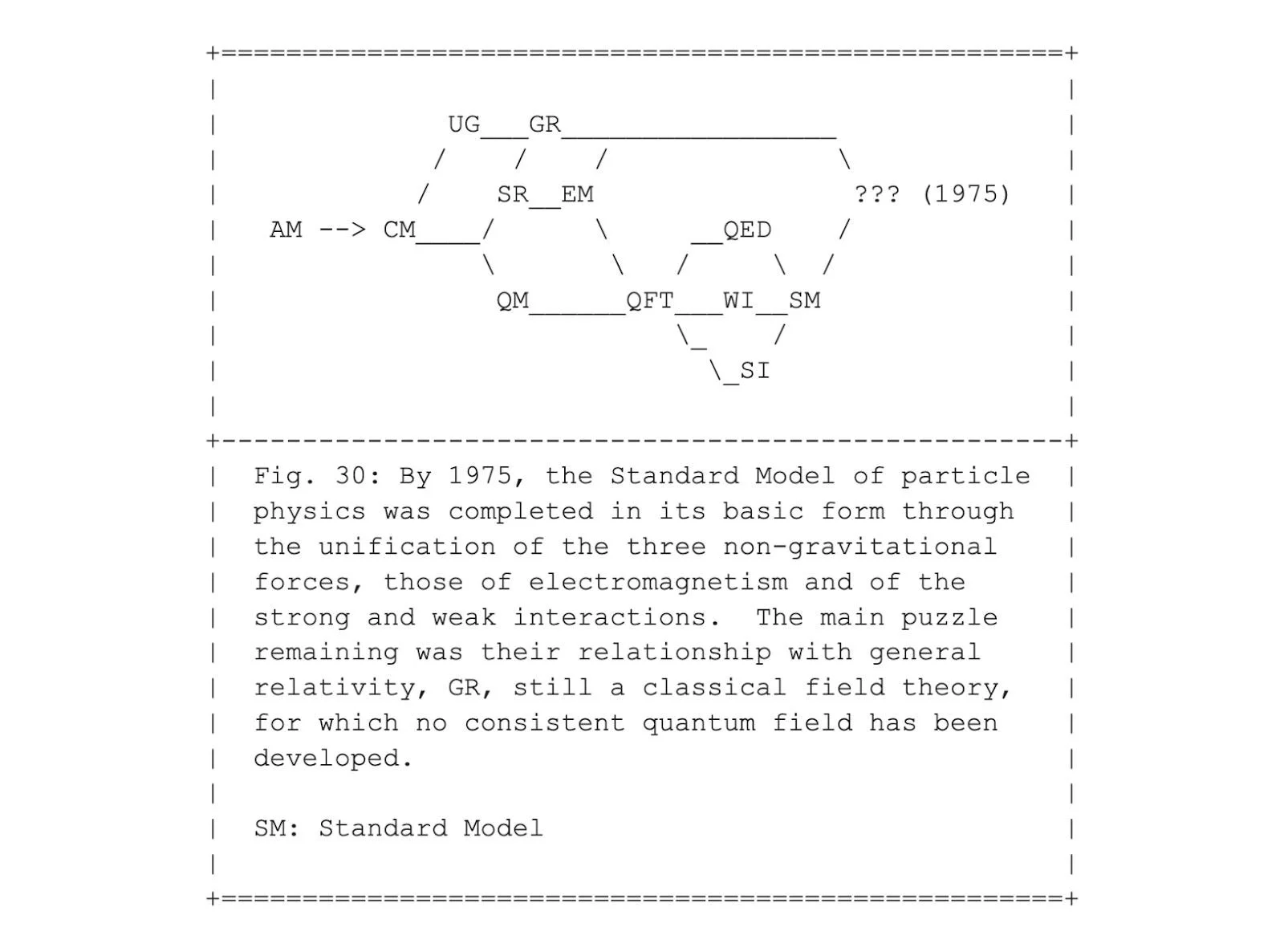

#012: The Standard Model of Particle Physics

#013: Our Journey So Far: Summary and Outlook

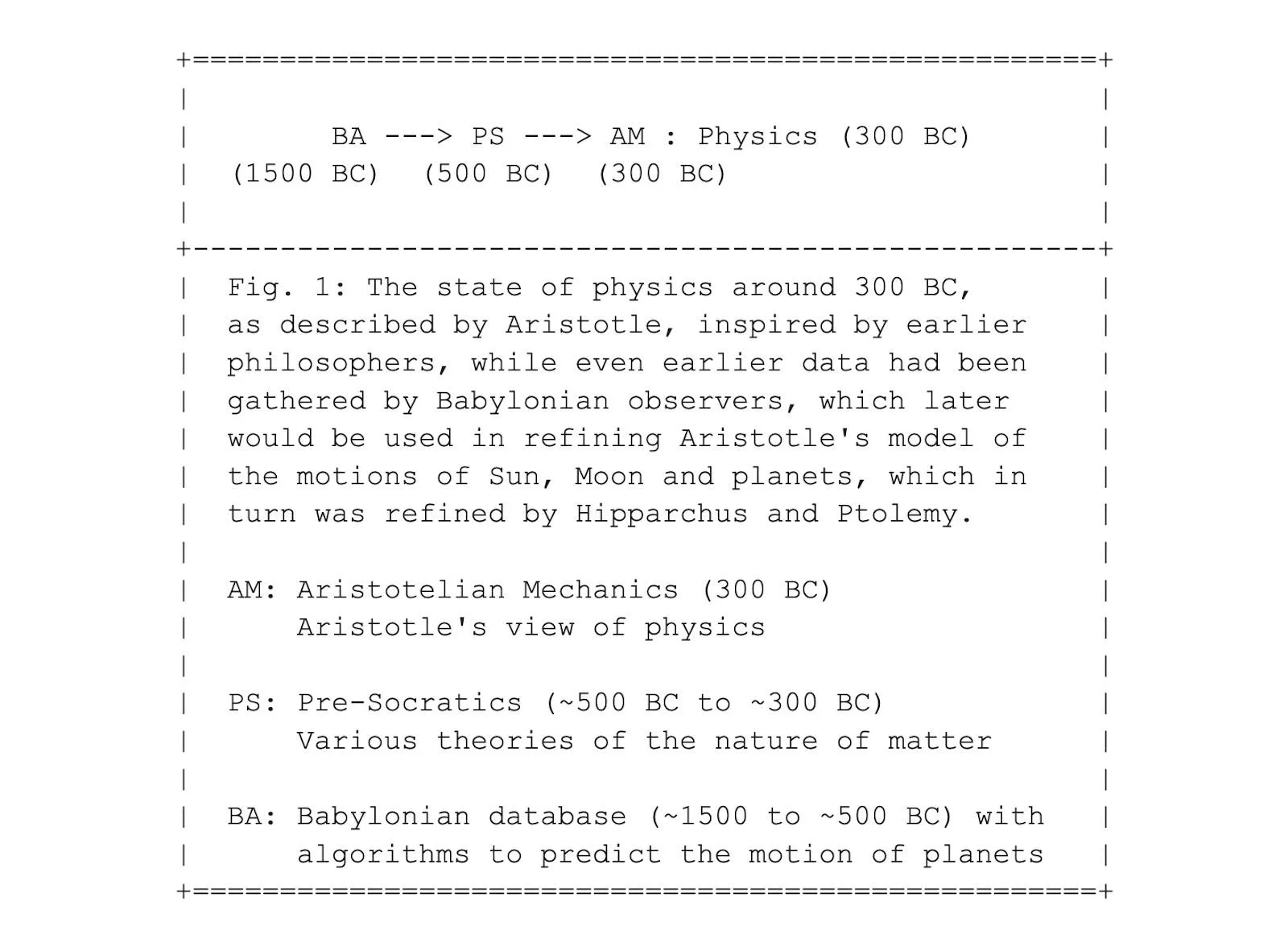

Fig 1

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #008

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

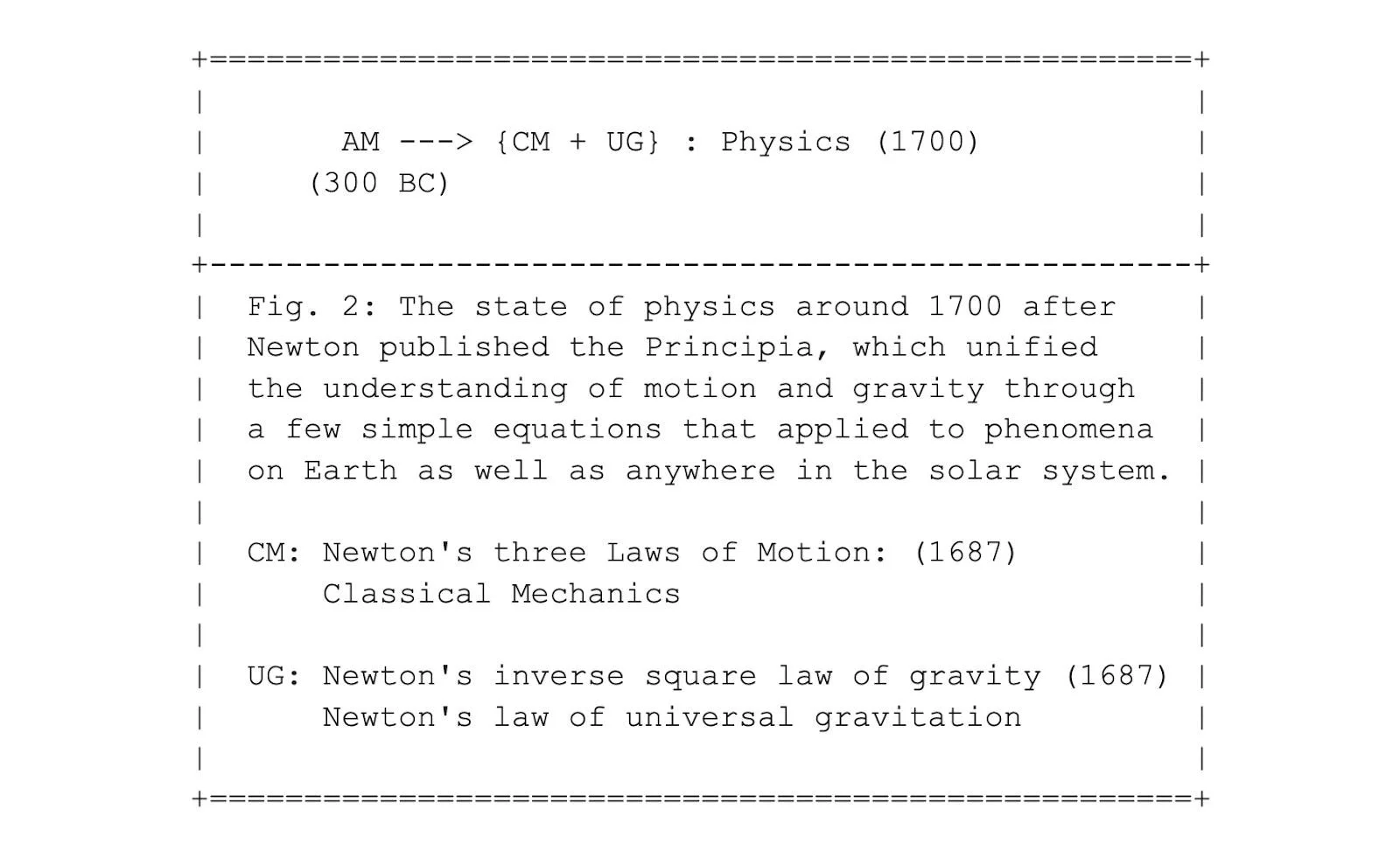

Fig 2

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #008

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

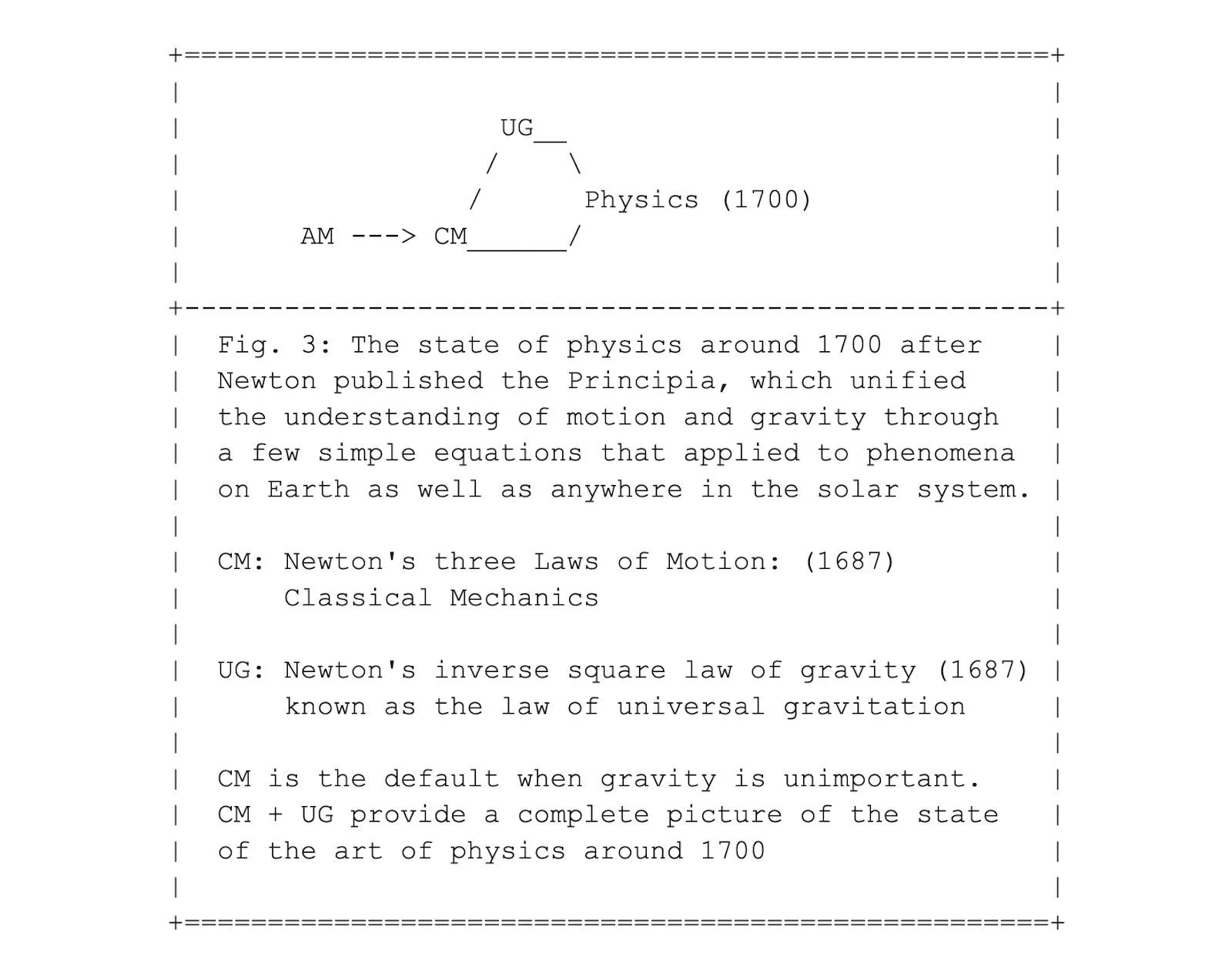

Fig 5

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #008

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

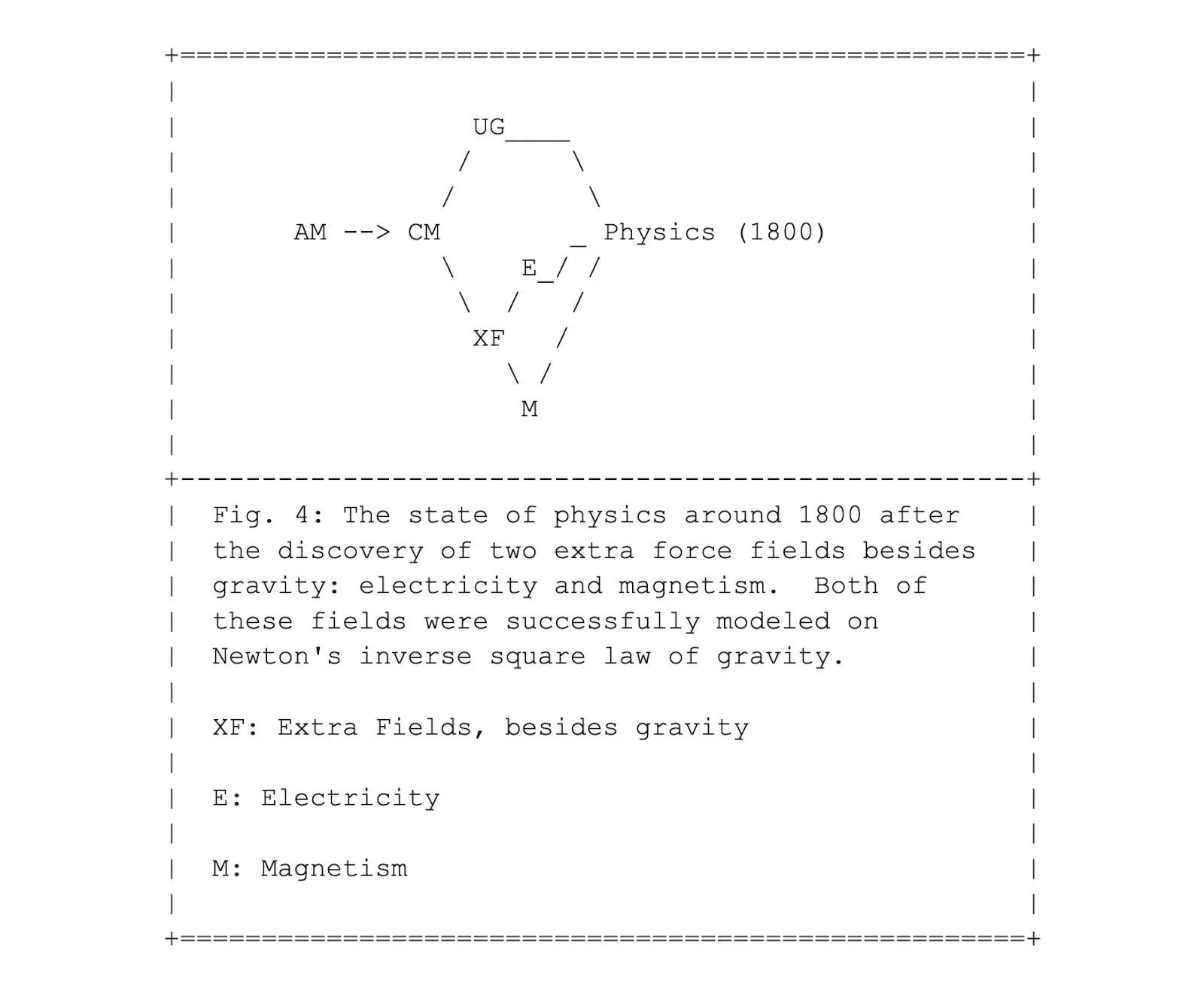

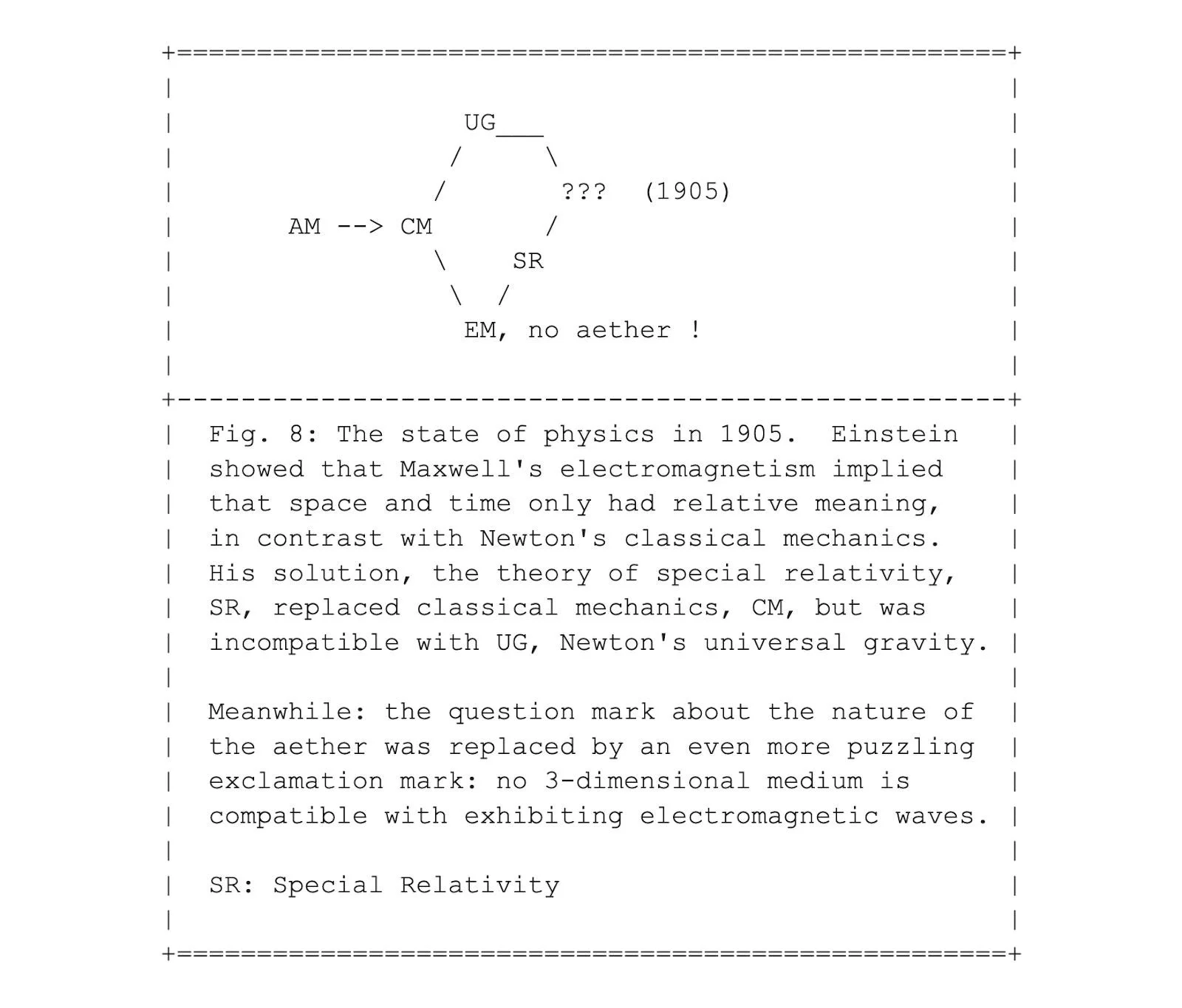

Fig 8

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 9

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

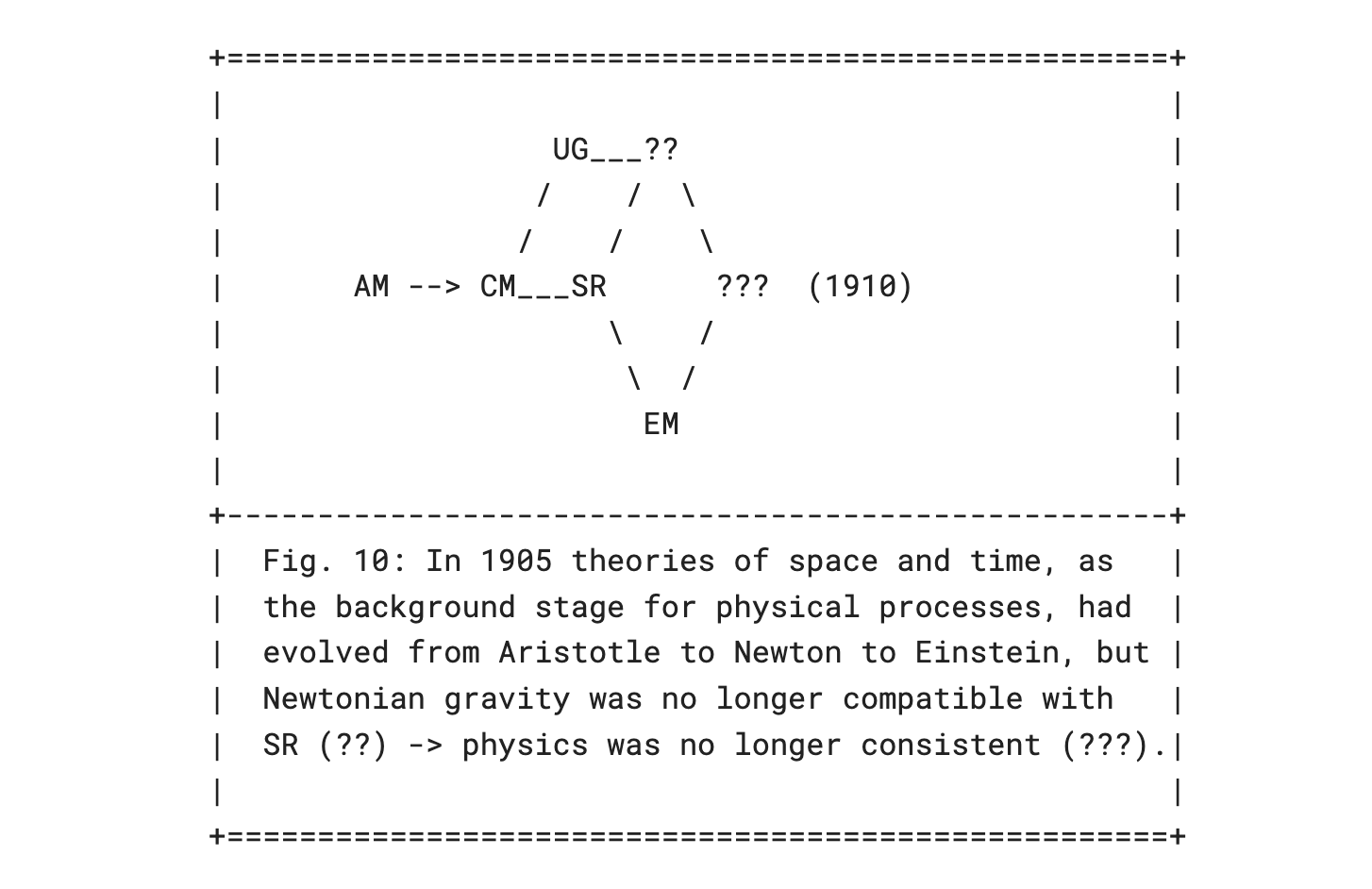

Fig 10

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

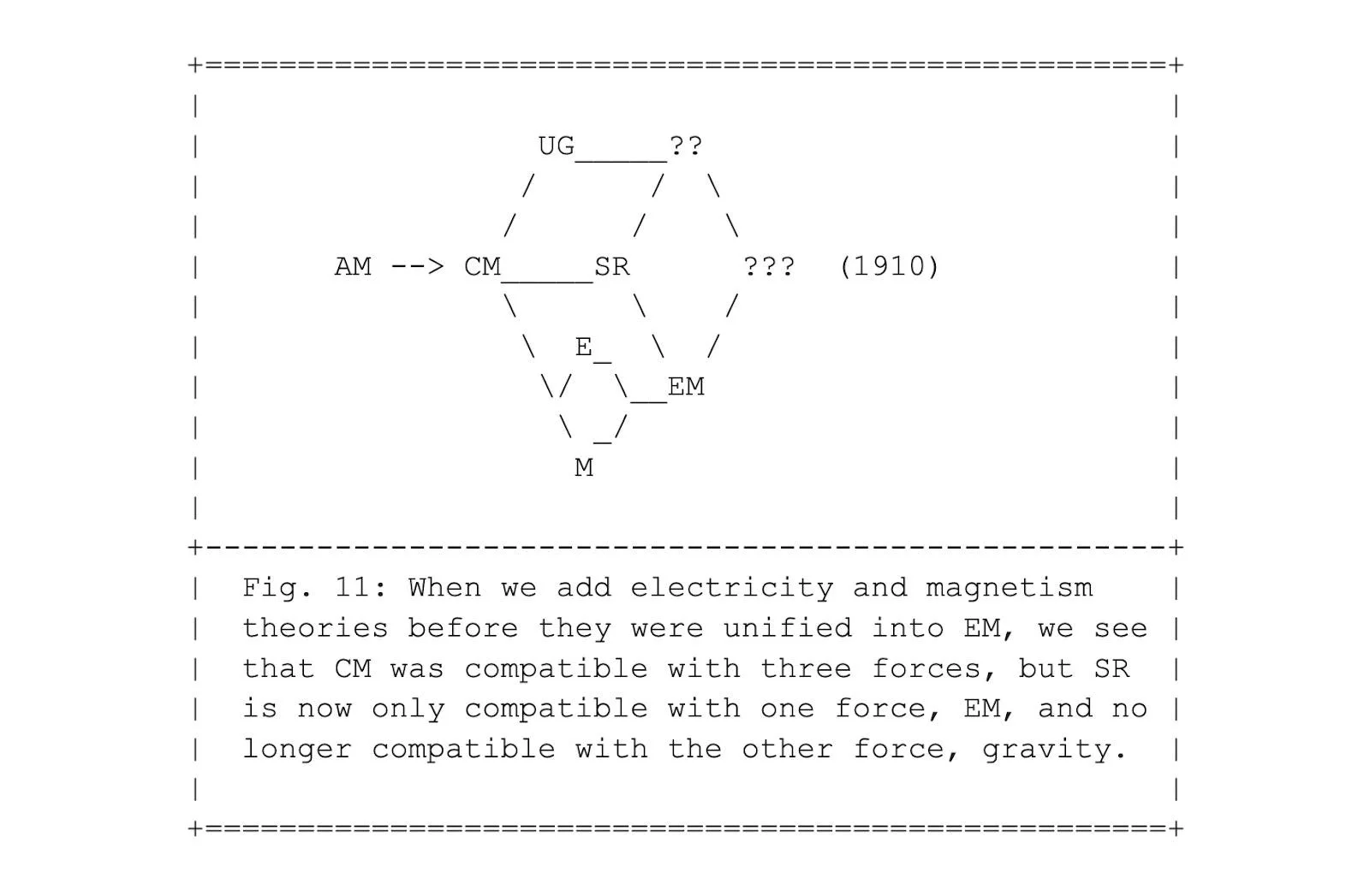

Fig 11

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

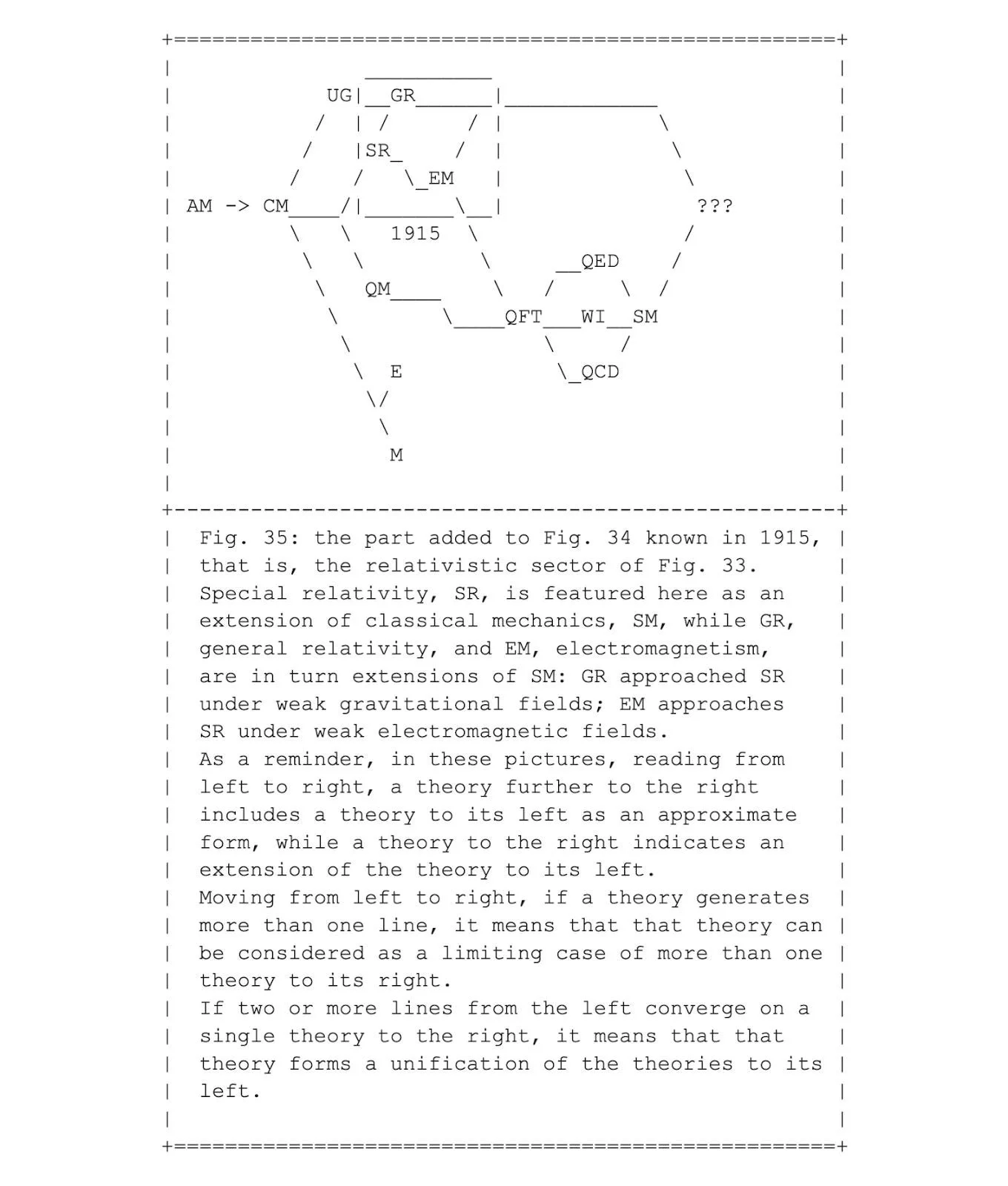

Fig 12

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

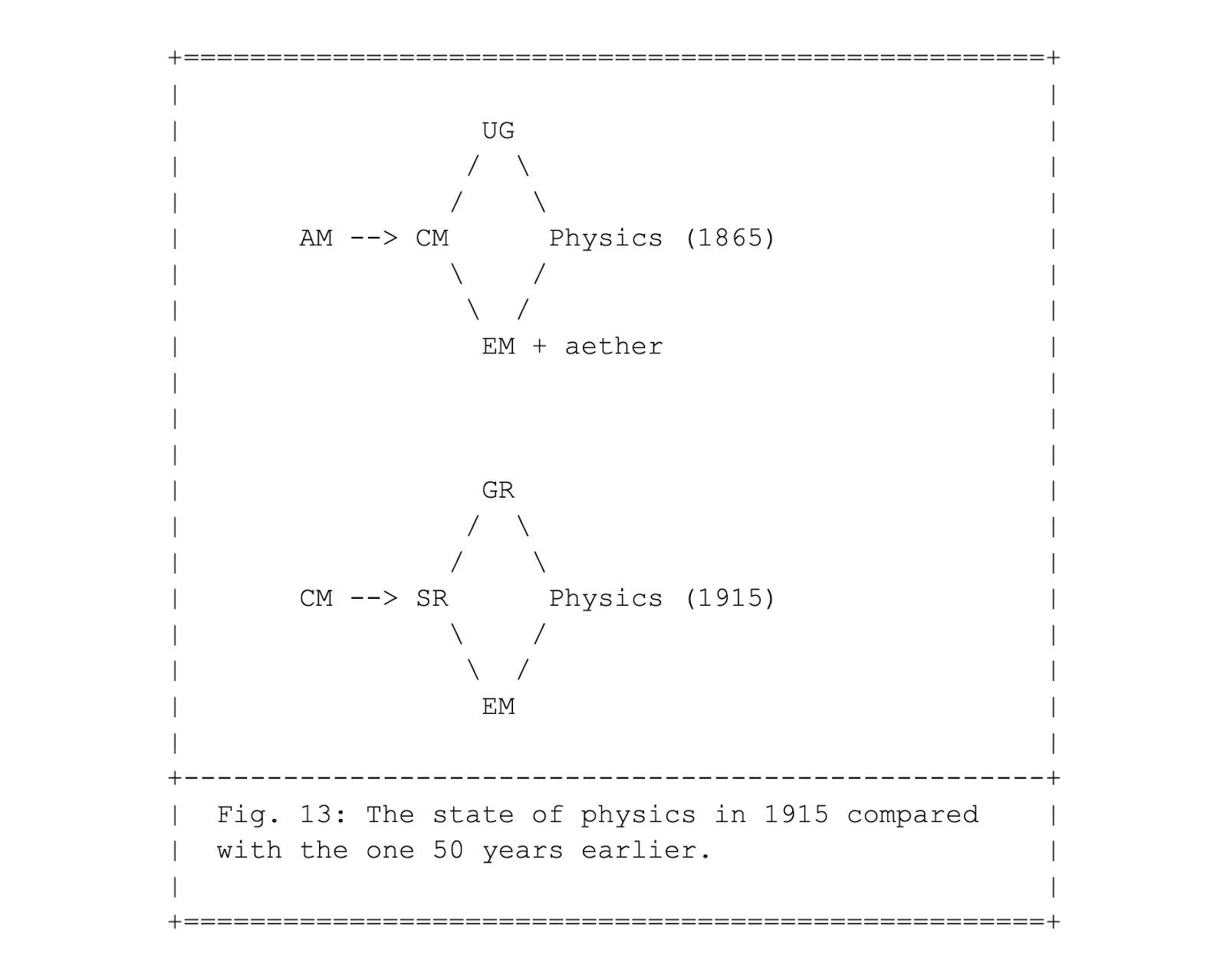

Fig 13

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

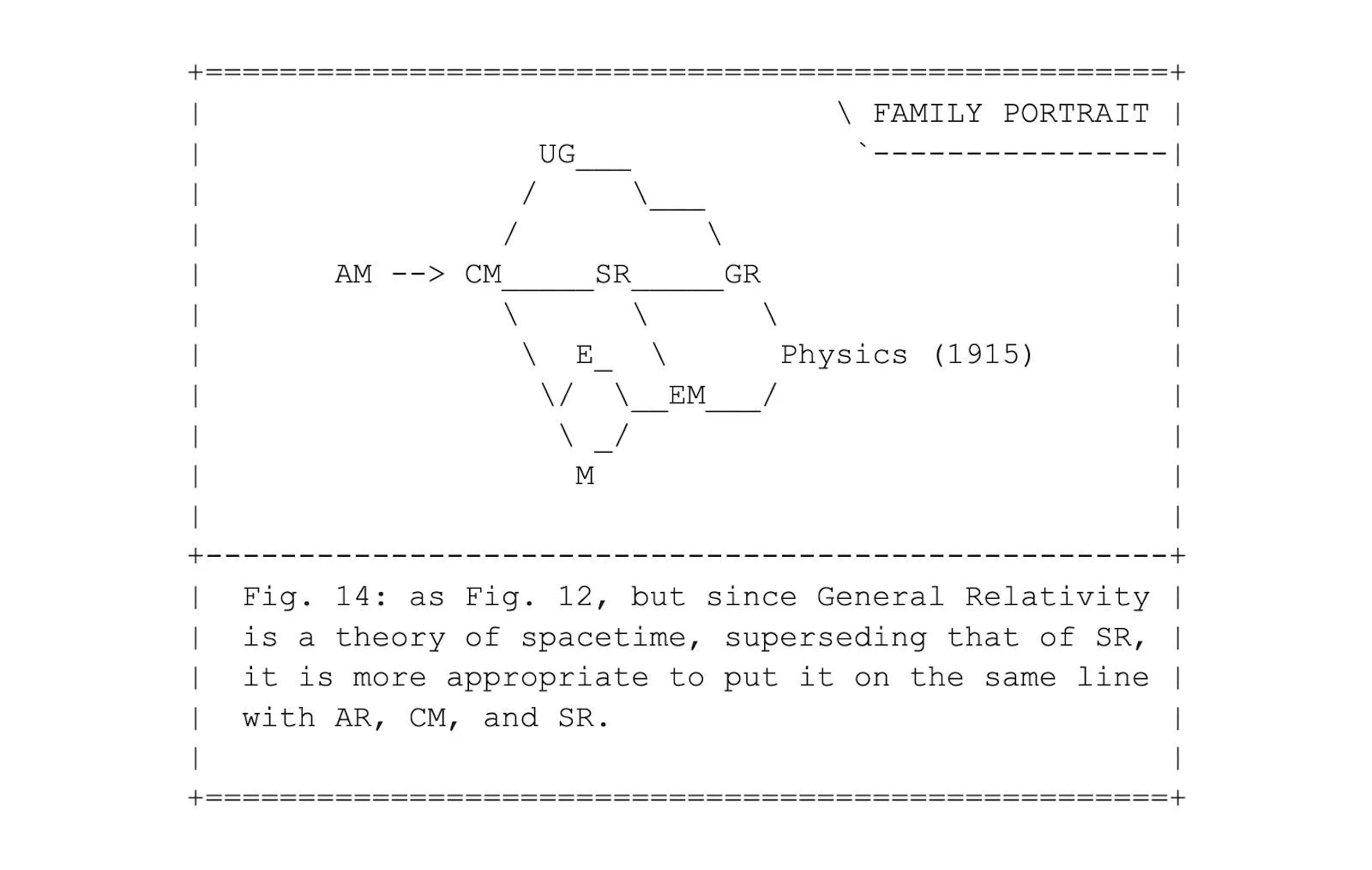

Fig 14

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

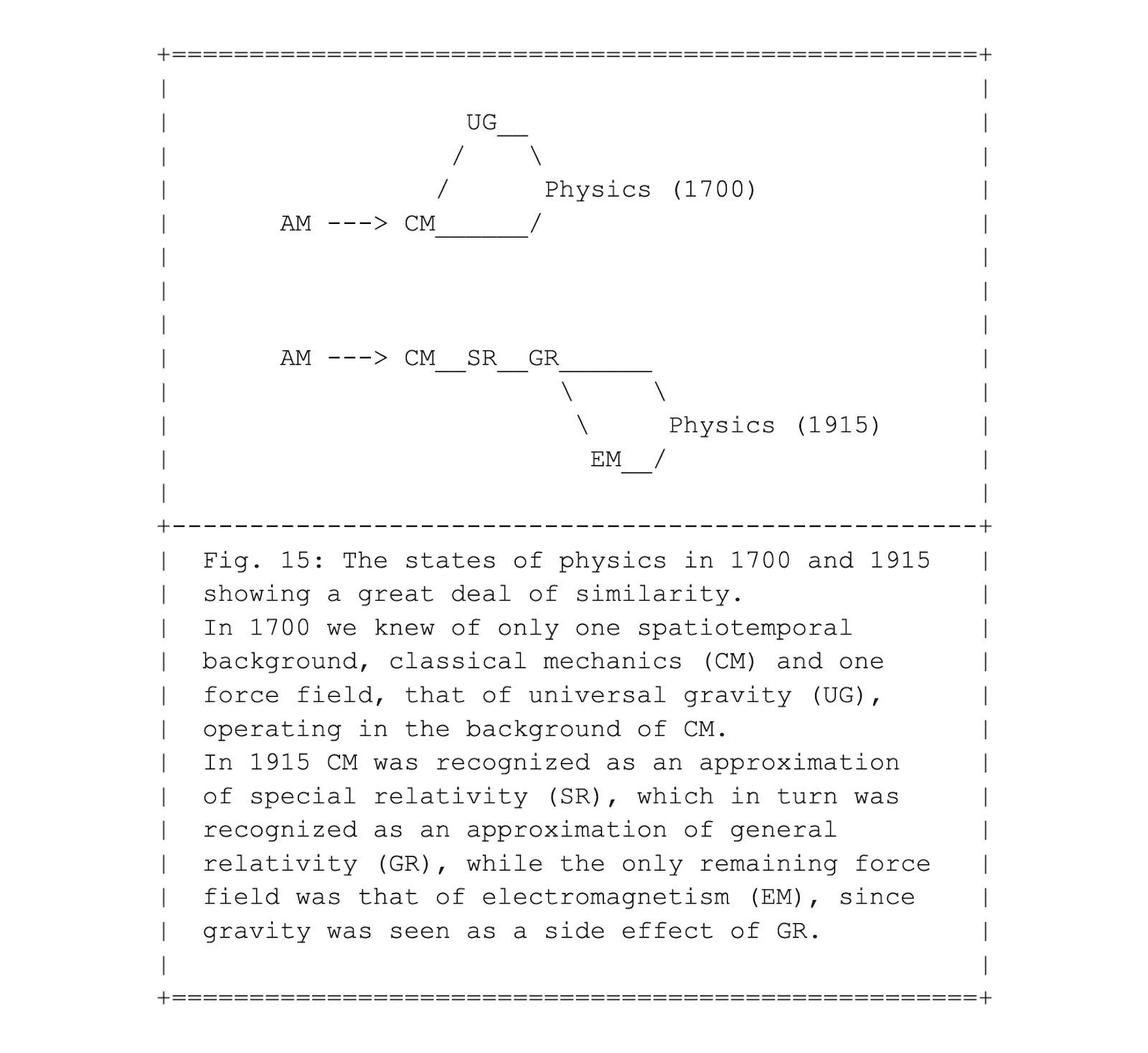

Fig 15

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 16

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 17

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #009

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

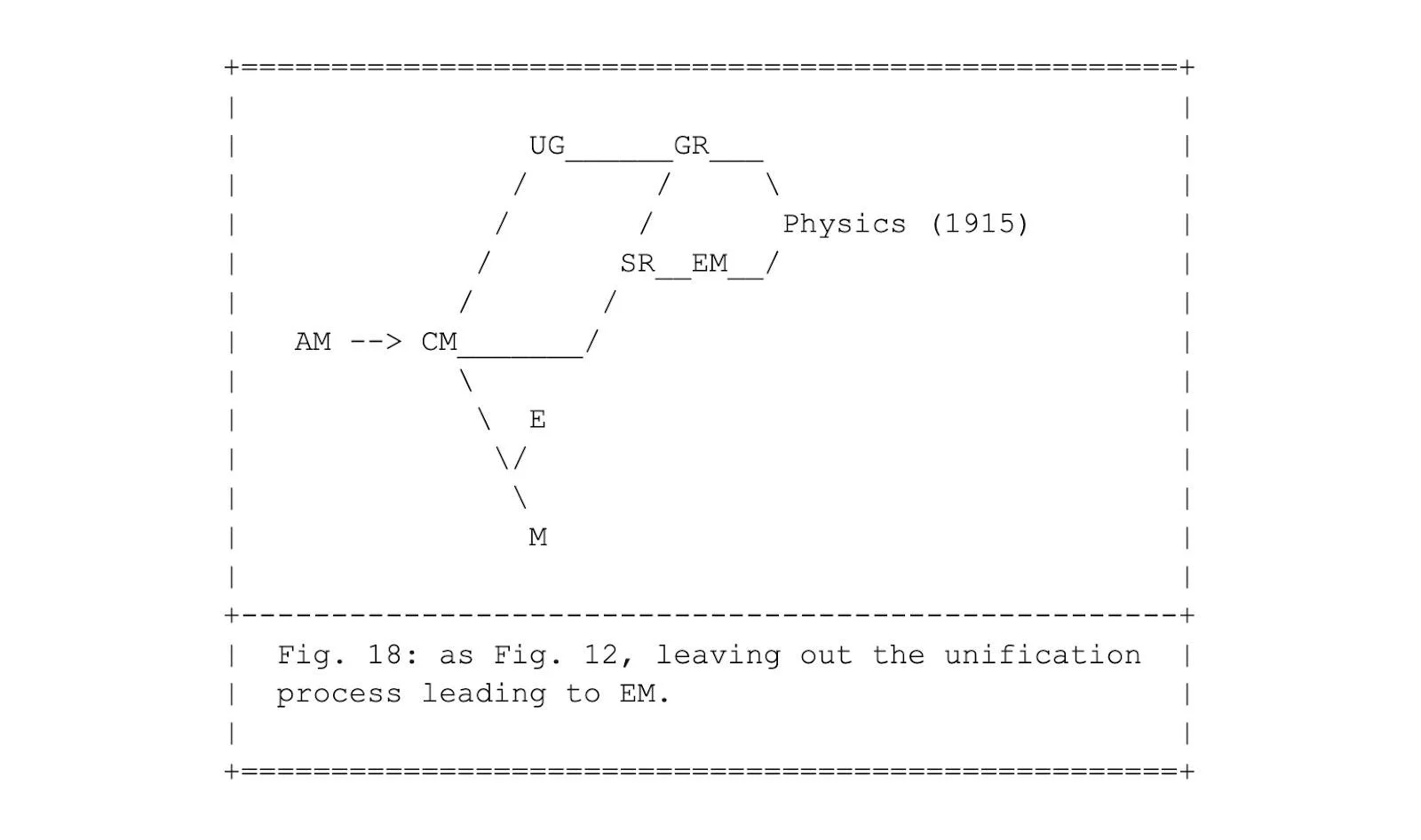

Fig 18

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #010

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

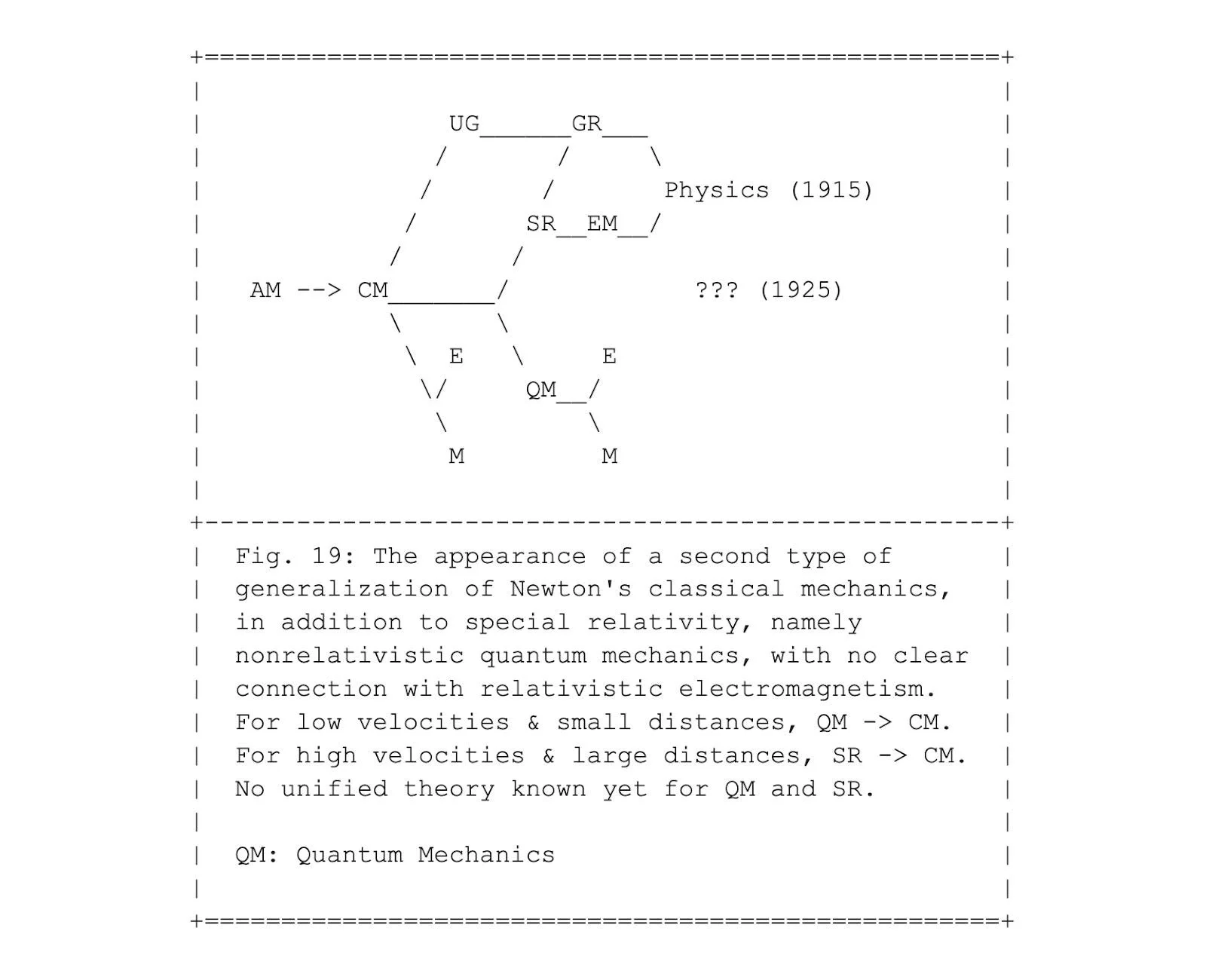

Fig 19

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #010

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

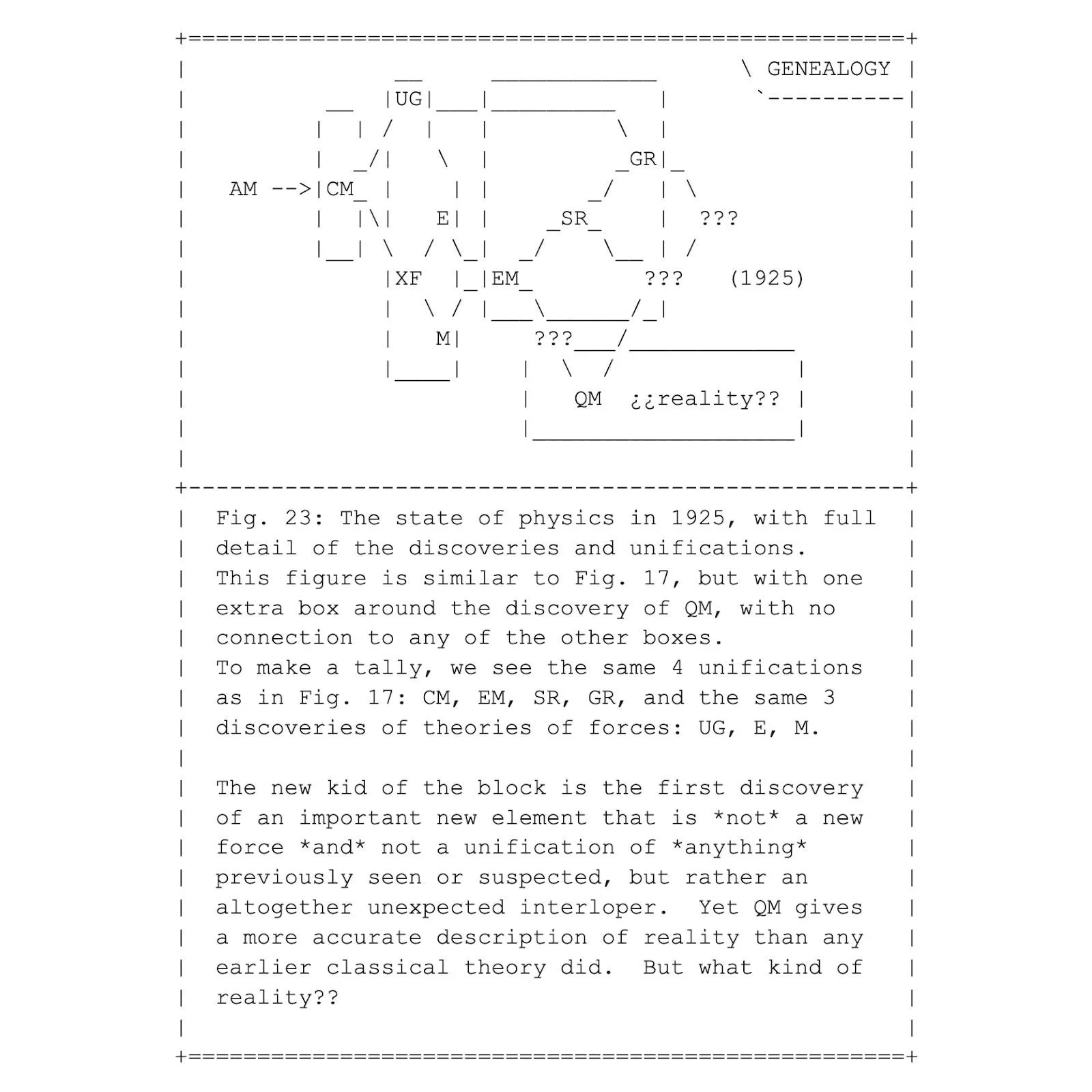

Fig 22

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #010

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

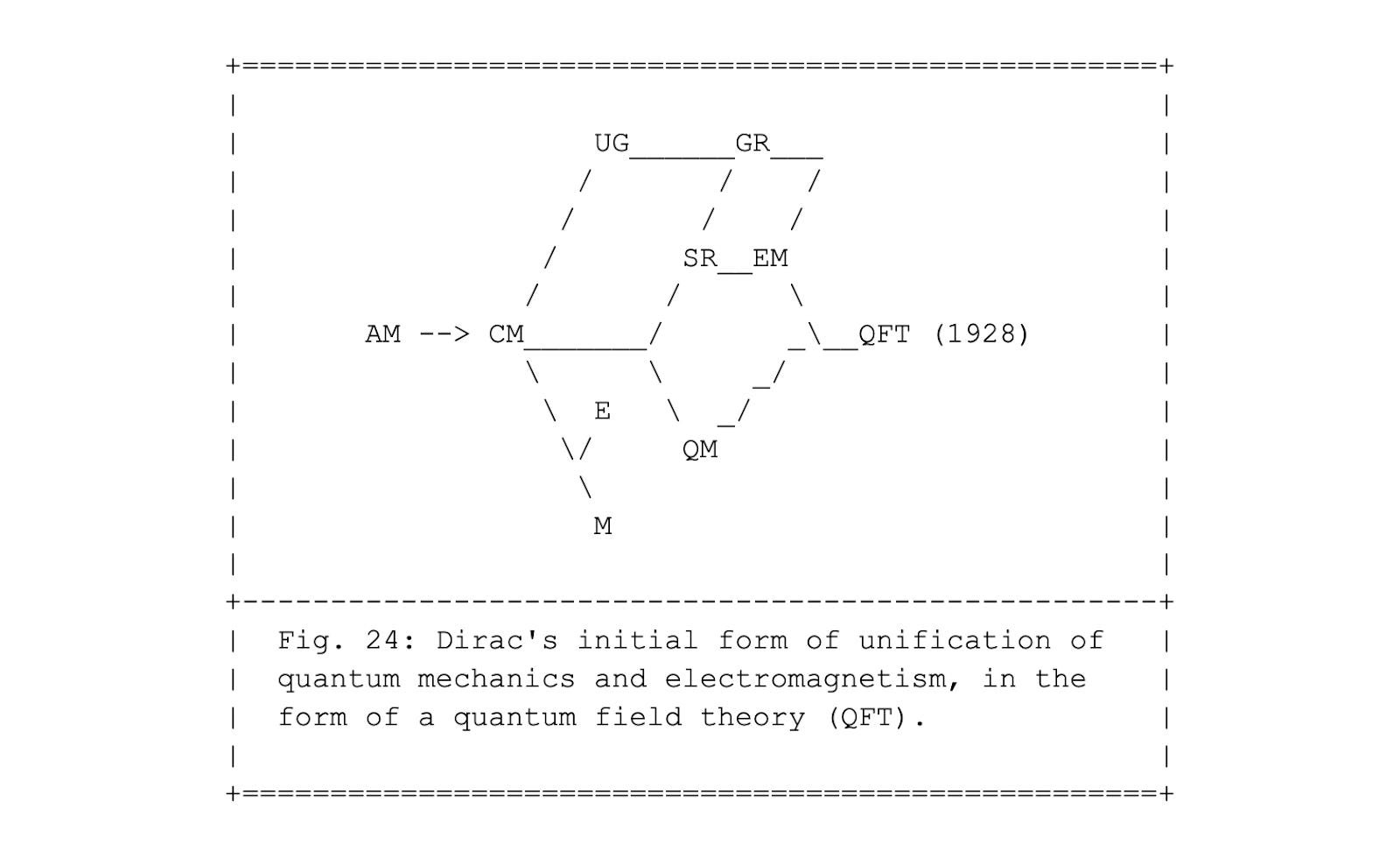

Fig 25

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #011

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 27

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #011

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

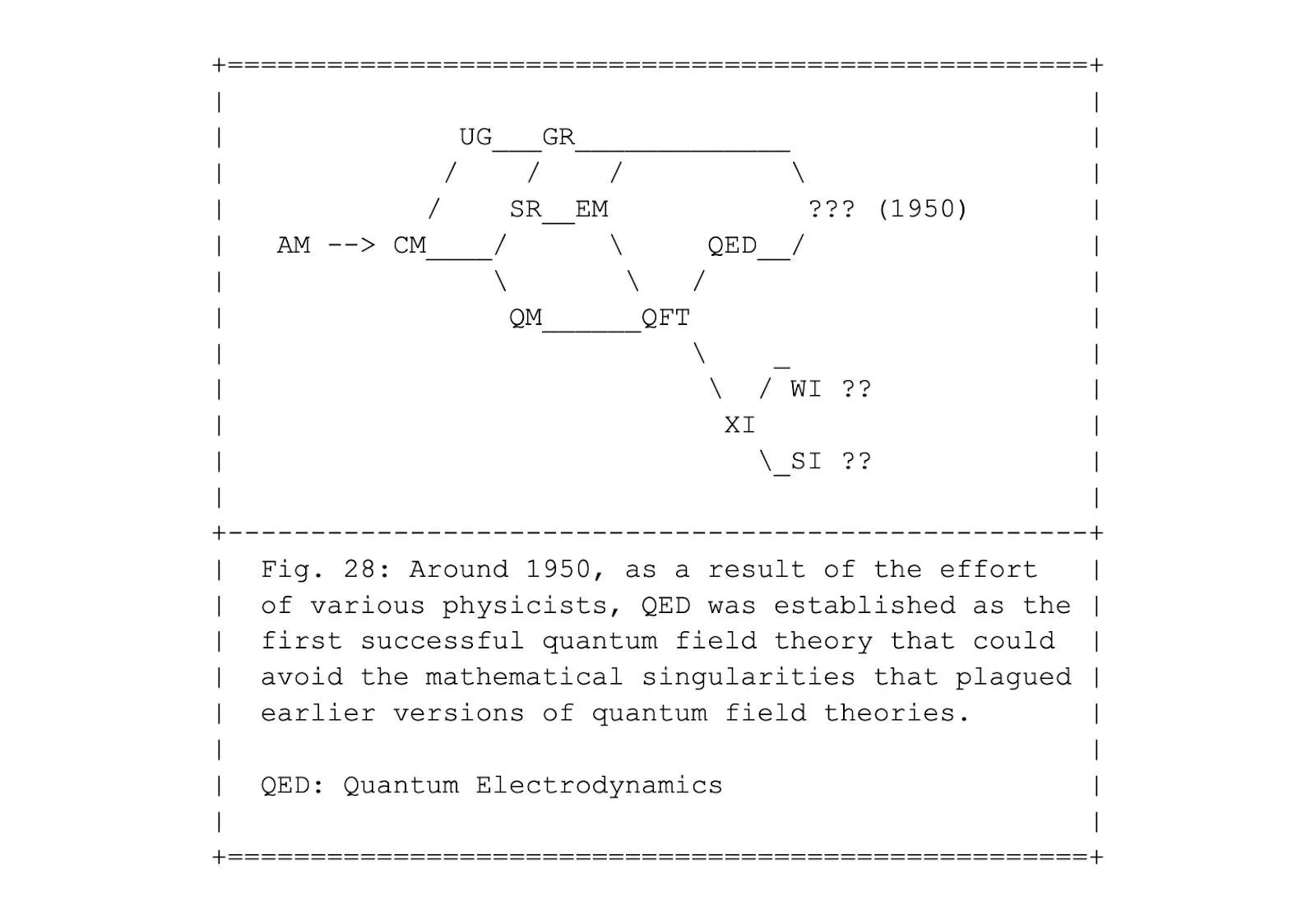

Fig 28

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #011

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Part 3: Inspiration From The History Of Contemplation

#014: Steps Toward a Science of Mind

#015: An Outline of The FEST Program

#016: Empirical Studies of the Mind

#017: Seeing the World through a Science Filter

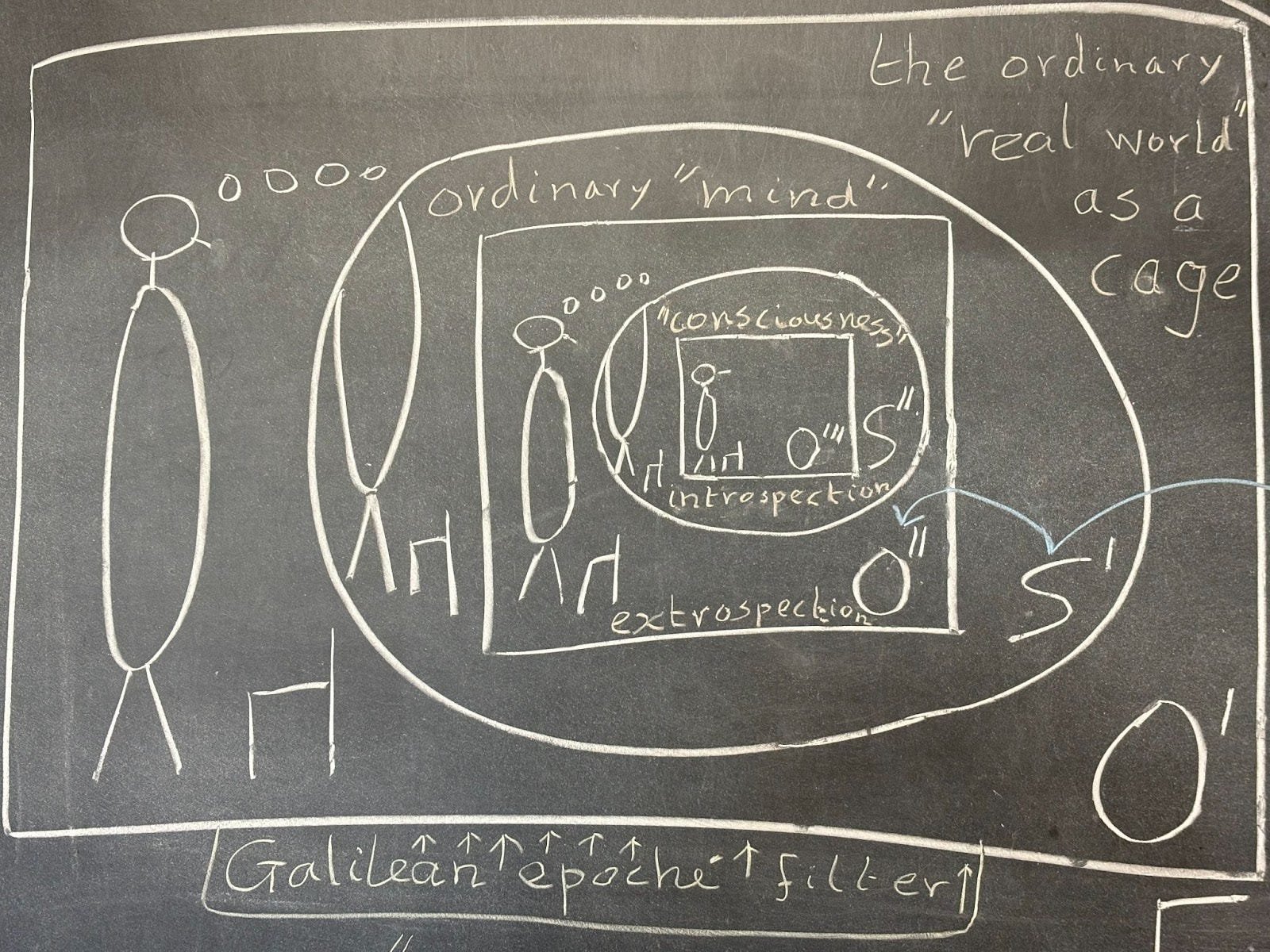

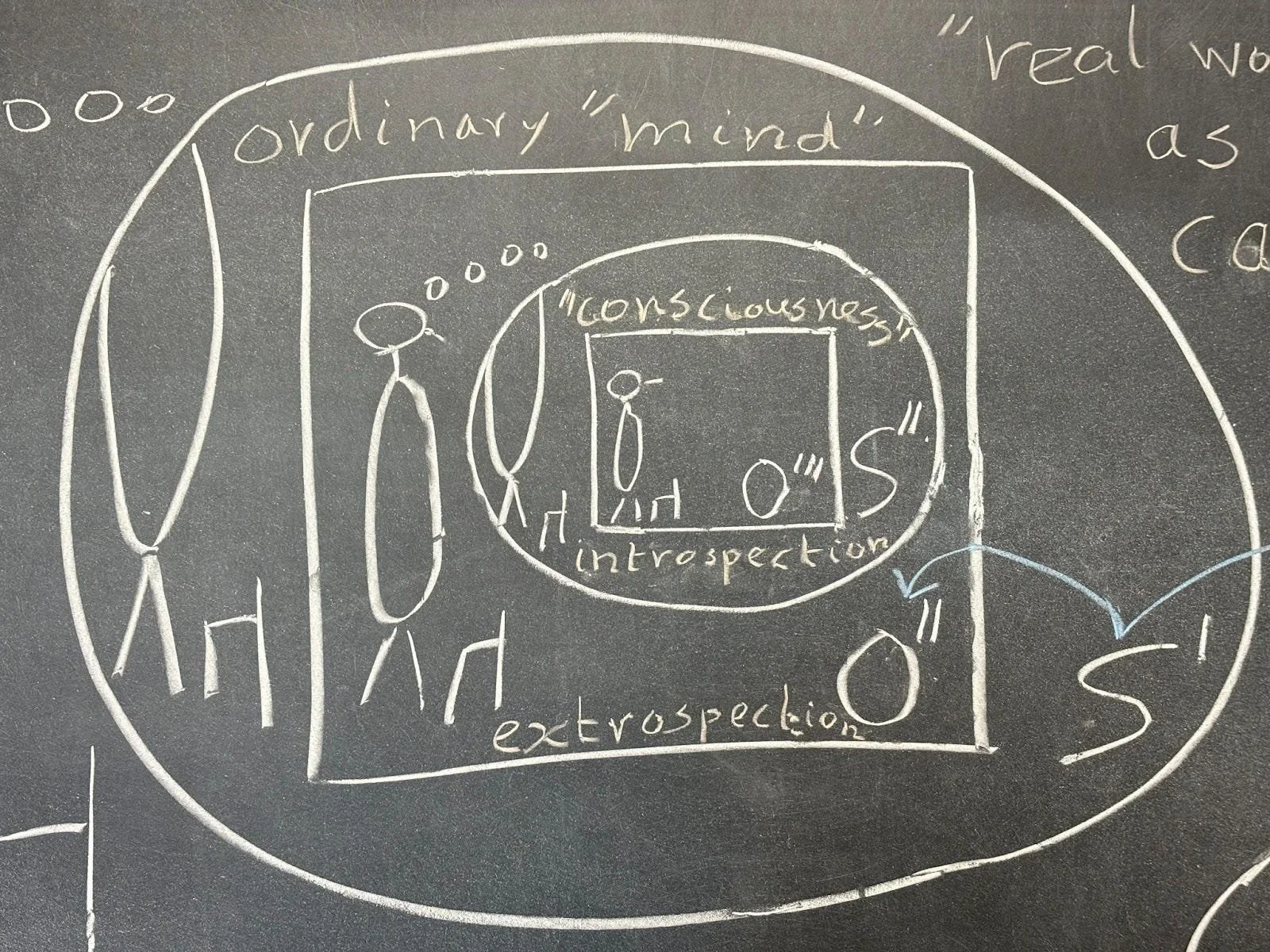

#018: A Mind in a World in a Mind in Reality

#019: Looking Through the Wrong End of the Telescope

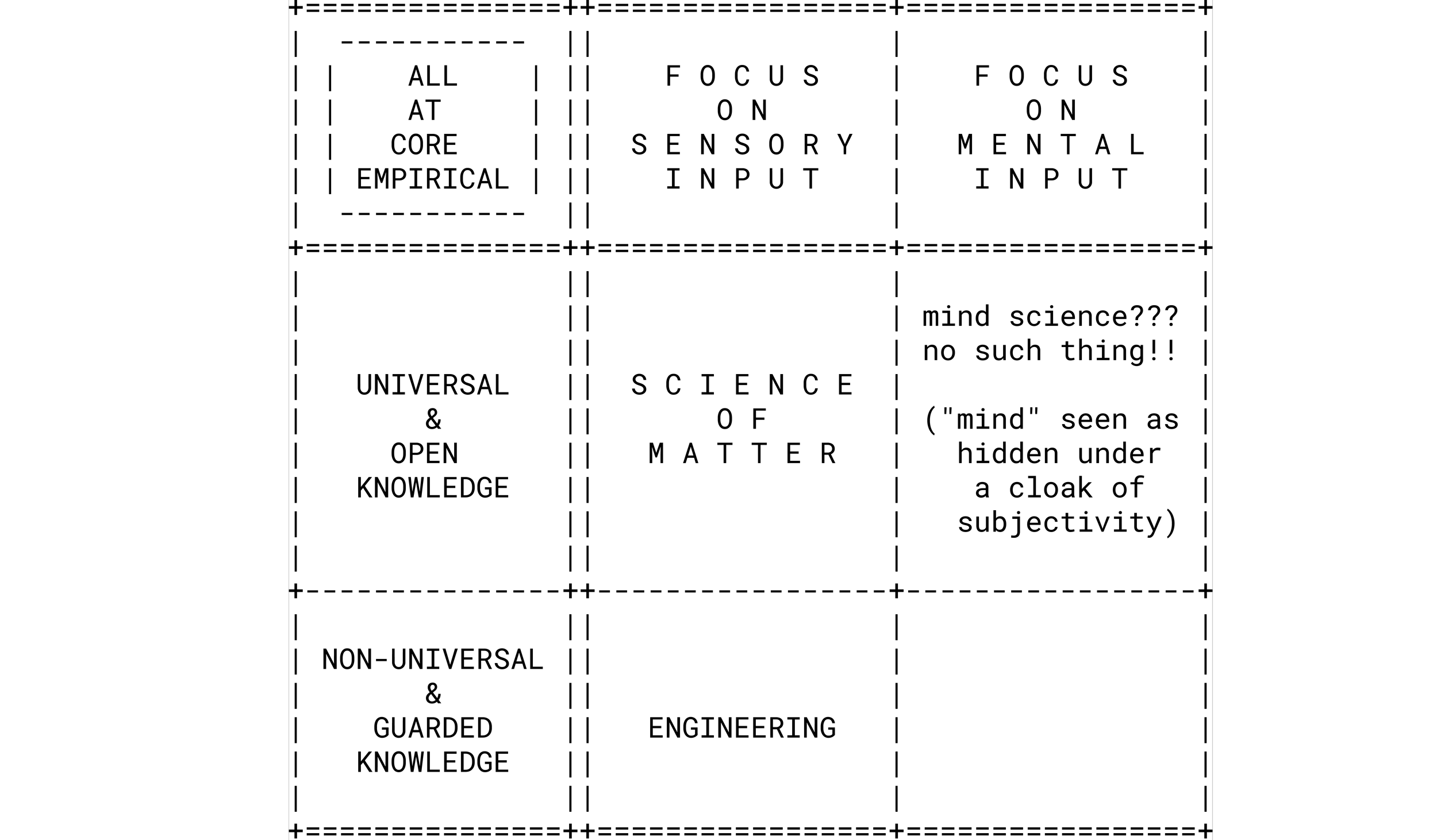

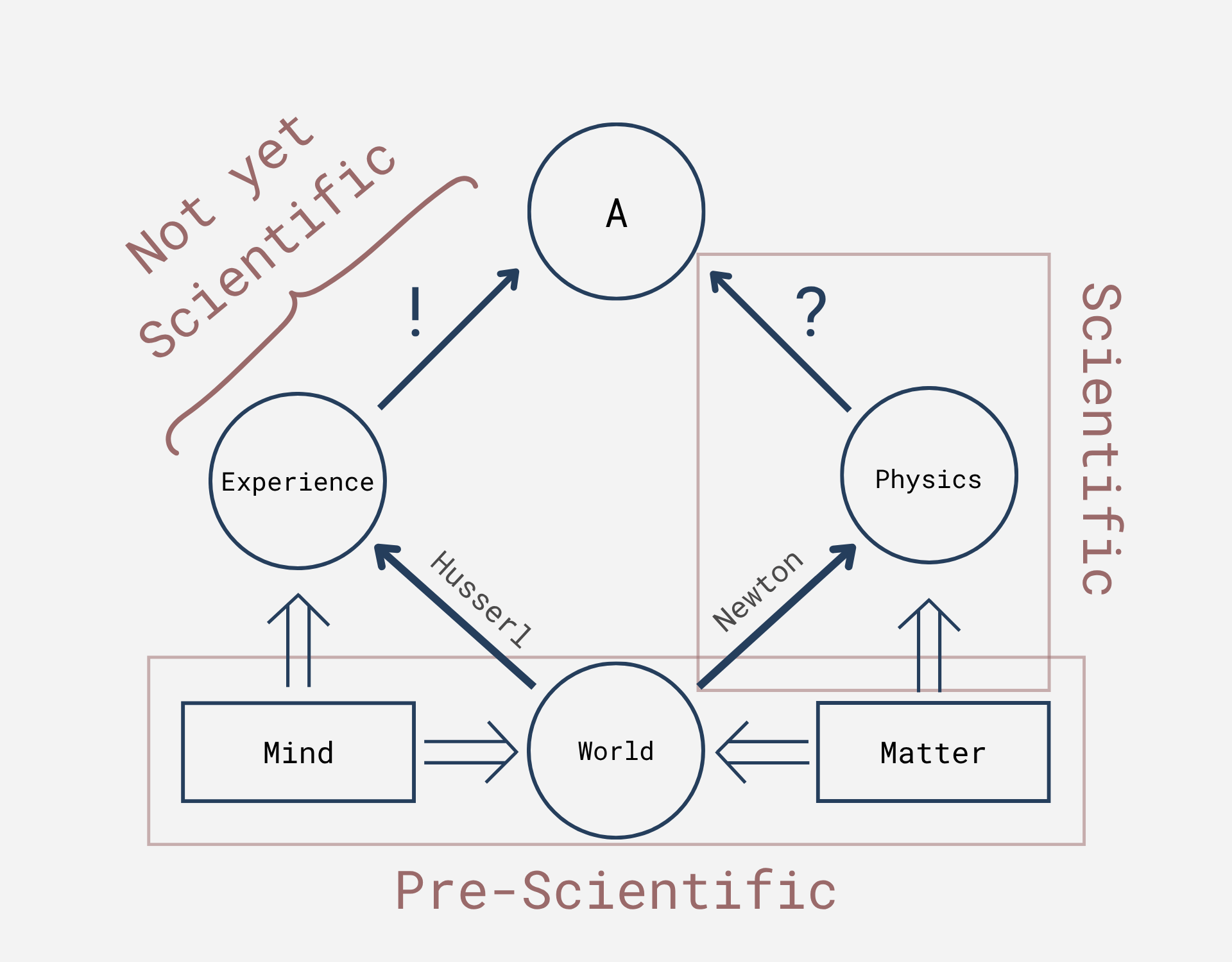

Fig 39

Here we start with the history of science of matter, natural science as it has developed over the last four hundred years. Even though the scientific method was qualitatively different from prescientific approaches like engineering, without the cultural knowledge base of the latter science could not have developed. Both science and engineering follow empirical methods of investigation. Here "empirical" is defined as being based on intersubjective experimental evidence. The meaning of the word stems from the Greek word εμπειρια, empeiria, experience.

Fig 40

Most scientists still seem to hold strong opinions about the "objective" nature of studies of matter, in contrast with studies of the mind which are deemed "subjective". In practice, both types of explorations rely on intersubjective peer review, if done in the right way. Not surprisingly the details are different when dealing with matter or dealing with mind. Only recently have there been glimmers of a turning of the tide, where the old objections included in the top right quadrant are losing some of their dogmatic appeal. Slowly "mind" is beginning to be invited to come out of an imposed hiding.

Fig 41

Among the branches of natural science, neuroscience attempts to look "under the hood" or more accurately "under the skull" to see how the brain, seen as the engine of consciousness, runs. By and large, the prejudice of the impossibility of an intersubjective empirical science of mind is sustained, when the only focus remains on a science of matter.

Fig 42

The mid nineties saw a quick rise in the popularity of studies of consciousness, and with that a growing awareness of potential pitfalls in the assumption that brains produce consciousness. An attractive relabeling of those pitfalls as the "Hard problem of consciousness" by David Chalmers accelerated the growth of a critical attitude towards the dogma that minds cannot be used to study minds in any serious way.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #014

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

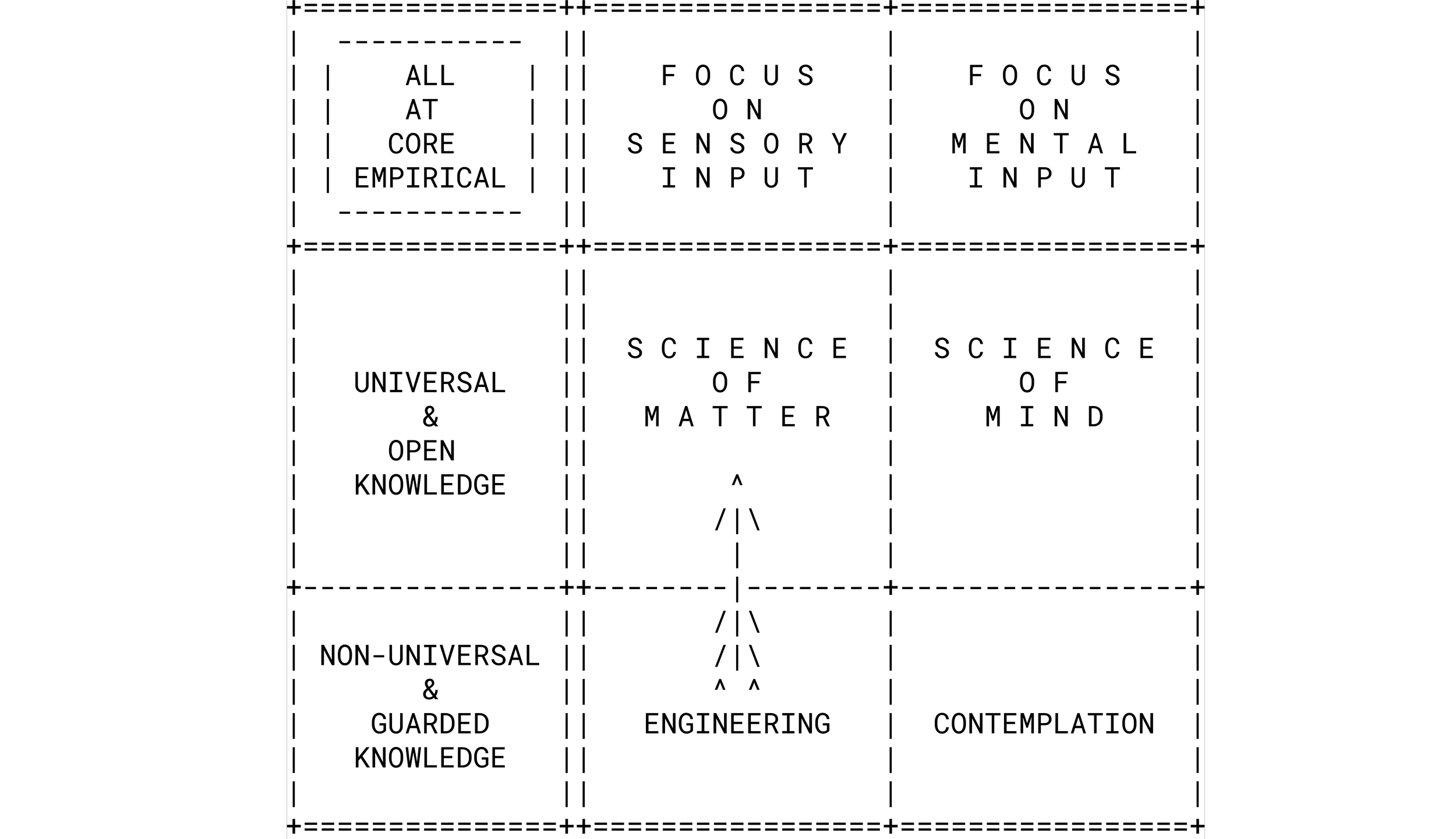

Fig 43

The main working hypothesis of the FEST program is that a science of mind, akin to the science of matter as pursued in natural science, is possible. The core point of this hypothesis is: a fully empirical exploration of mind, using mind itself as a tool, can be as "objective", in practice intersubjective, as natural science.

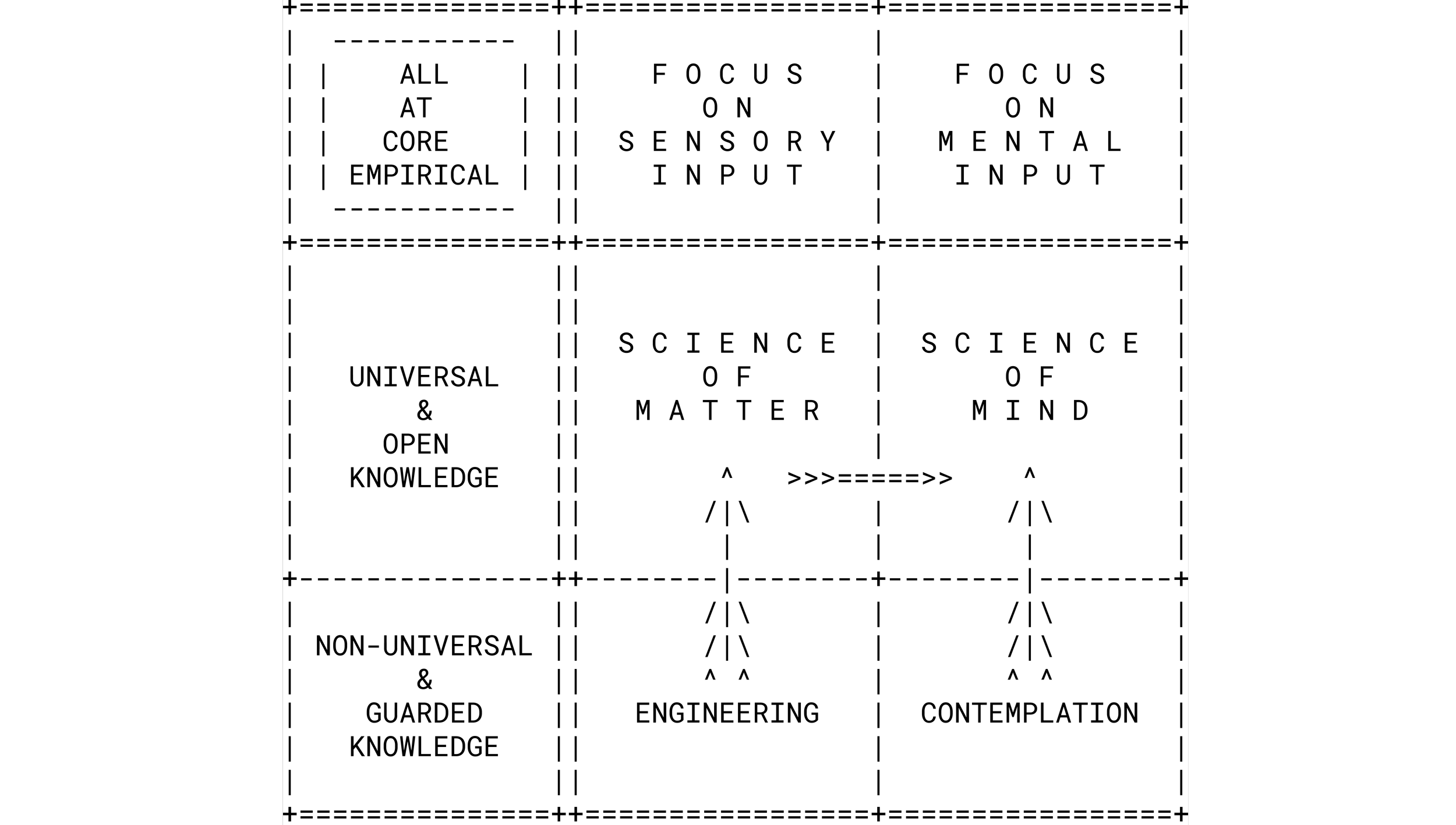

Fig 44

Here the full 2x2 content of the matrix is completed. Contemplation is depicted as a prescientific forerunner of a science of mind, in parallel with engineering as a prescientific forerunner of the science of matter.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #015

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 45

Science incorporates two principles that are missing in prescientific engineering. The first one is the use of working hypotheses, based on suspension judgment, in particular suspending all forms of belief and disbelief. The second is a global self-governing community of peers that provides quality control, independent of outside influences. Even so, those two additions could only find traction in the presence of extensive databases, compiled in earlier periods, which provided the initial knowledge to build upon.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #015

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 46

The most logical way to set up a simple version of a science of mind is to emulate the successful first steps of the science of matter, as pursued by Galileo and others, up to Newton. Undoubtedly, many differences will be encountered along the way. However, as long as we hold onto the core methodology of science, while putting all other aspects of natural science as practiced so far in question, we can hope to strike a pragmatic balance.

Fig 47

For the first time, all four quadrants are now connected. For a science of mind, this means that a few millennia of written literature are available, of traditions focusing on studies of matter, or of mind, as well as on both.

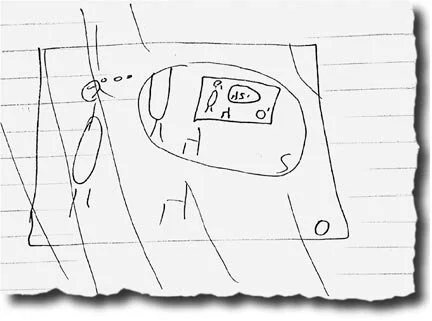

Fig 49

The original figure caption in the New York Times article in 1997 read: Dr. Piet Hut, a physicist, offers this sketch: the objective world (O), with person and chair; the subjective experience of the world (S), in the balloon; the empirical understanding of the world, including physics (O’), in the smaller rectangle; and the empirical understanding of subjective experience, including psychology, (S’), in the really small balloon. Dr. Hut argues that when S and S’ are conflated, confusion reigns.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #016

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

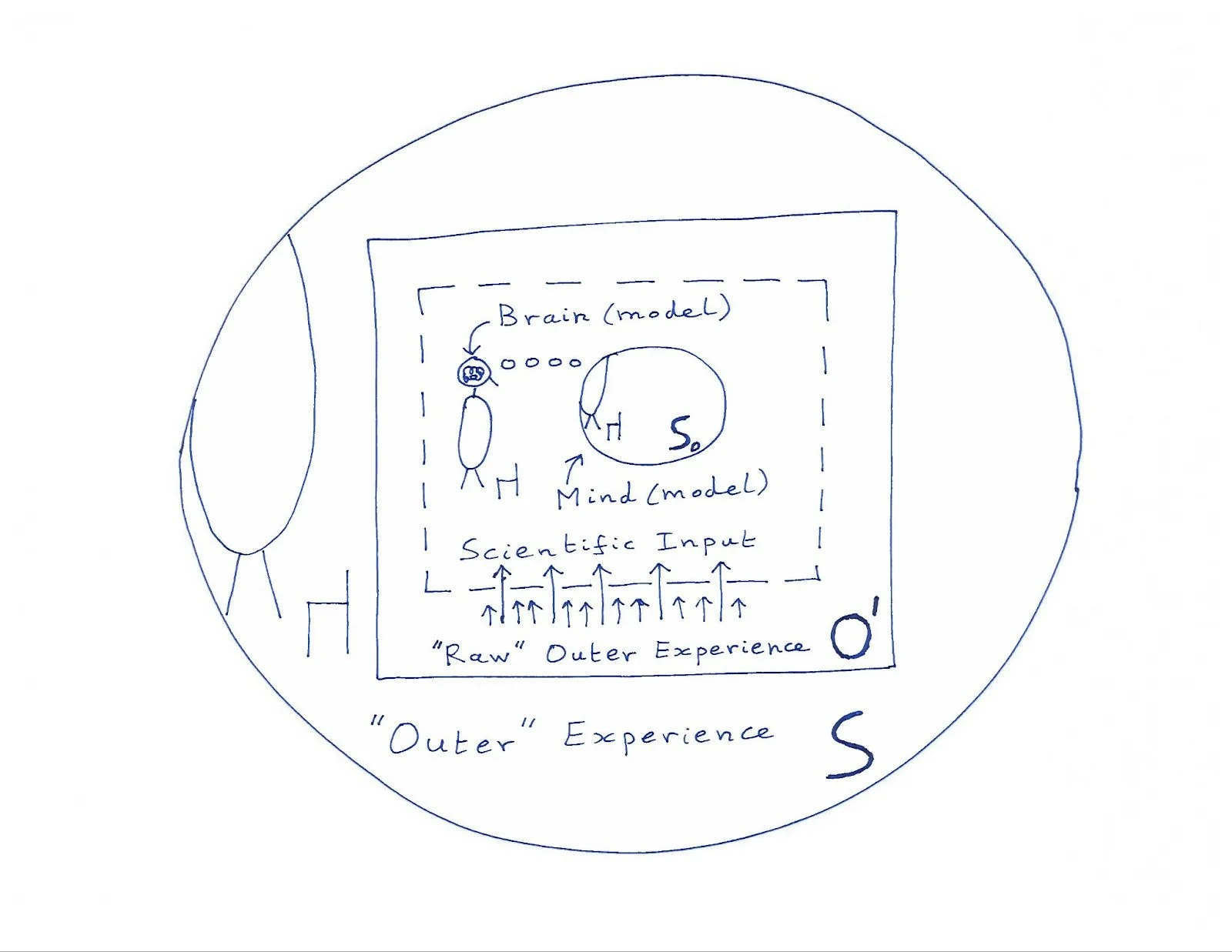

Fig 50

In addition to the areas of S depicted in Fig. 49, we have added here an outer shell labeled "inner experiences", and an inner box within the box O', separated by a "science filter" from the rest of O'.

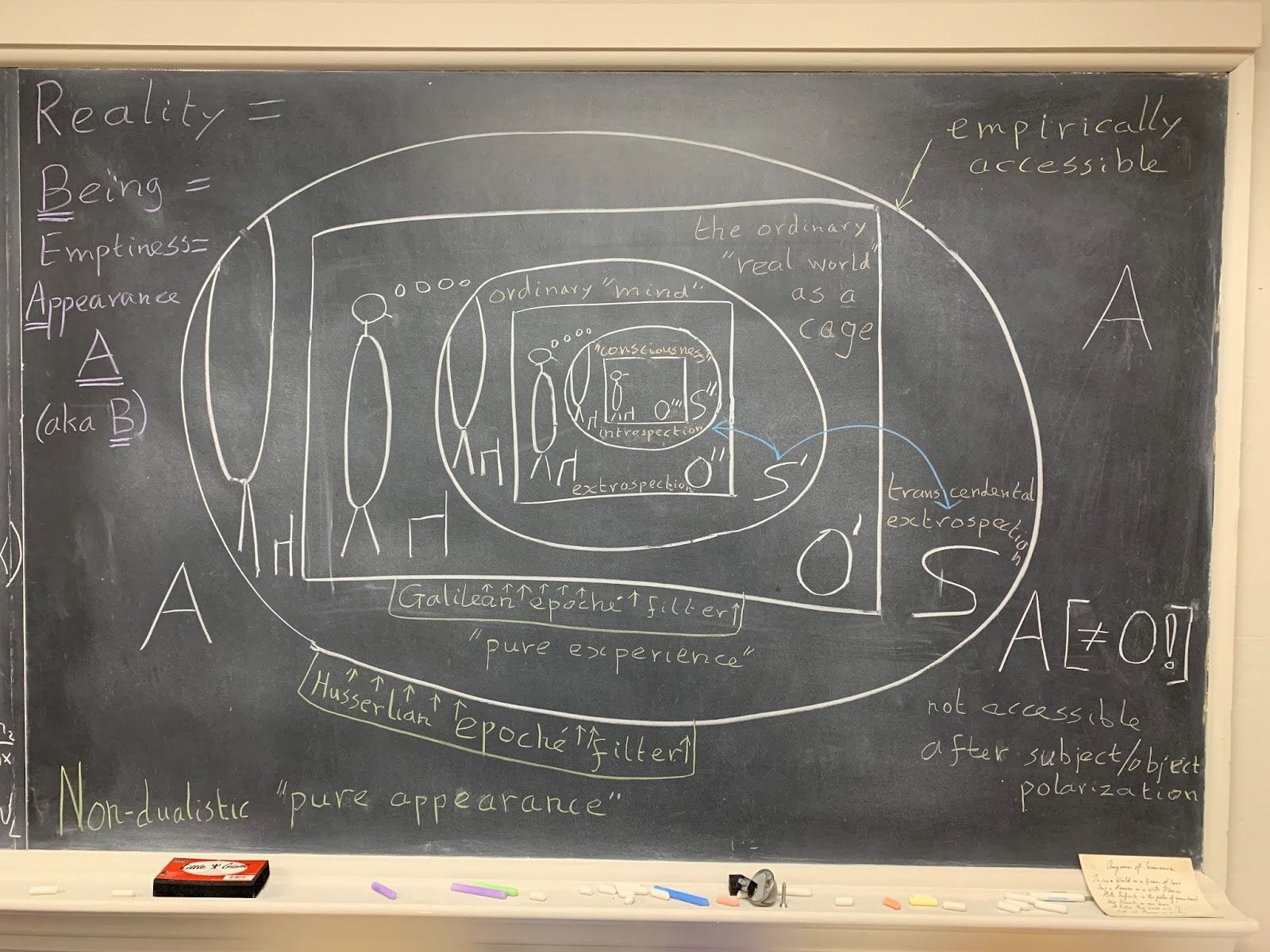

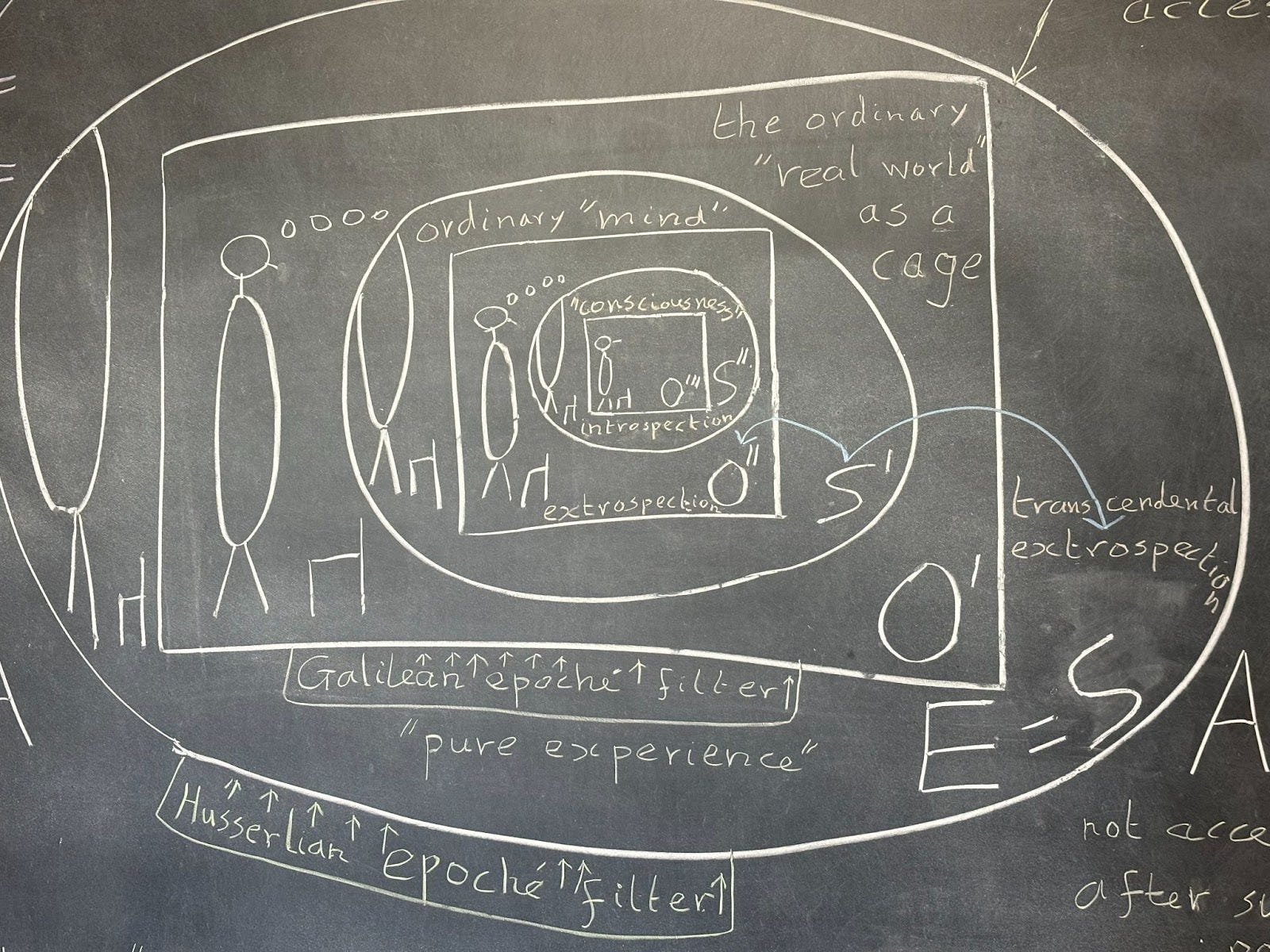

Fig 51

A "sneak preview" of a view of reality that accommodates a nondual view in the outer area labeled A. It features a subject-object polarizing filter separating S, the mind as we normally use it, from the broader perspective of A, which encompasses the entire blackboard area. Further details to be provided in the next few entries.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #017

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

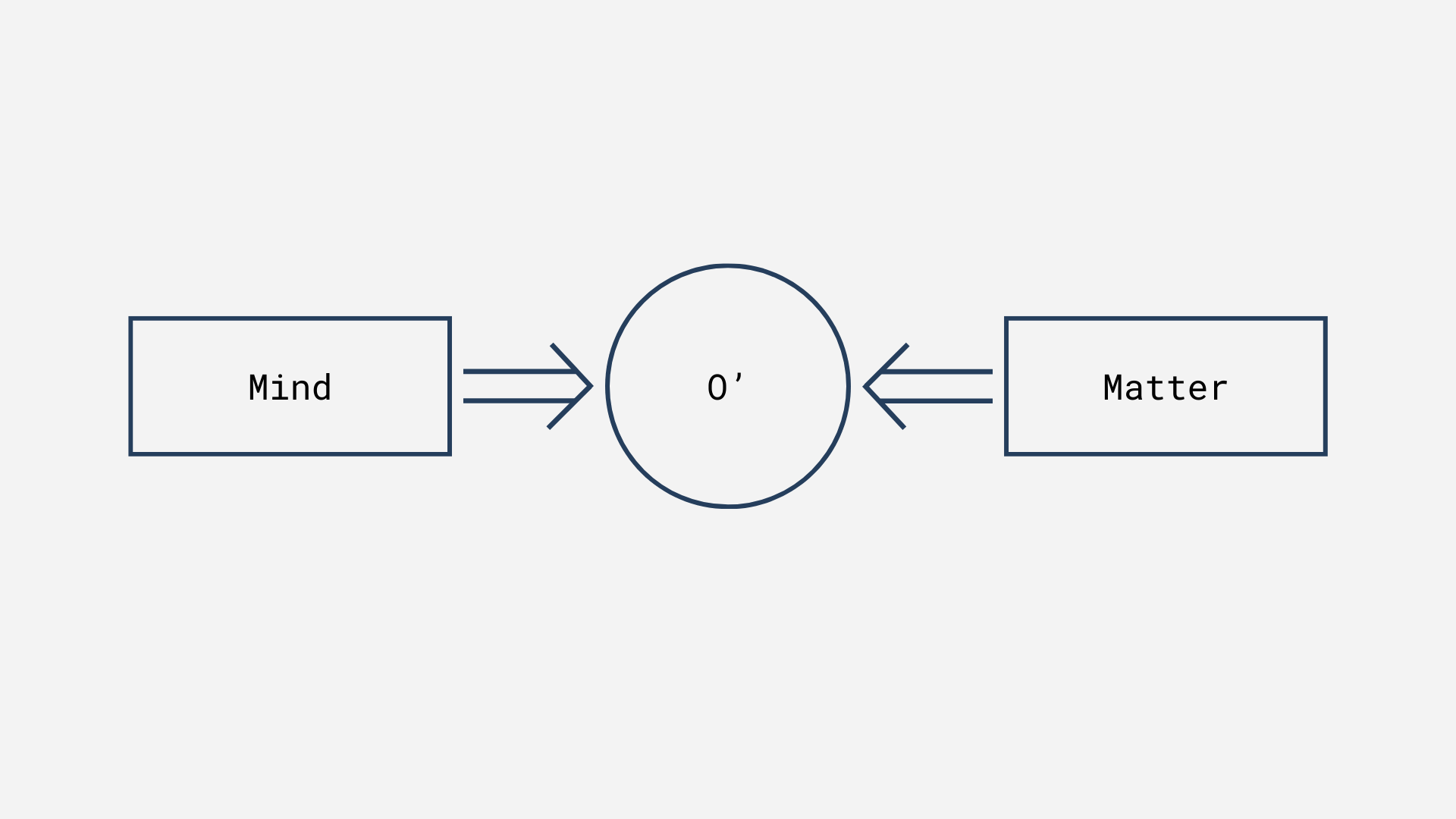

Fig 54

The ordinary world O', a representation we believe in as if we are dealing with the real thing.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #018

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Part 4: A Unification Of Sciences Of Matter And Mind?

#020: Beyond Empirical Studies

Fig 58

A handshake between the non-philosophical and non-scientific every-day life view of the world and the analysis we made of the world as given in O'.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #021

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 59

A reminder that O' in Fig. 58 represents the world, and as such is given in our mind S.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #021

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 60

The naive ontology of Fig. 57 translated into the epistemology used in Part 3.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #021

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

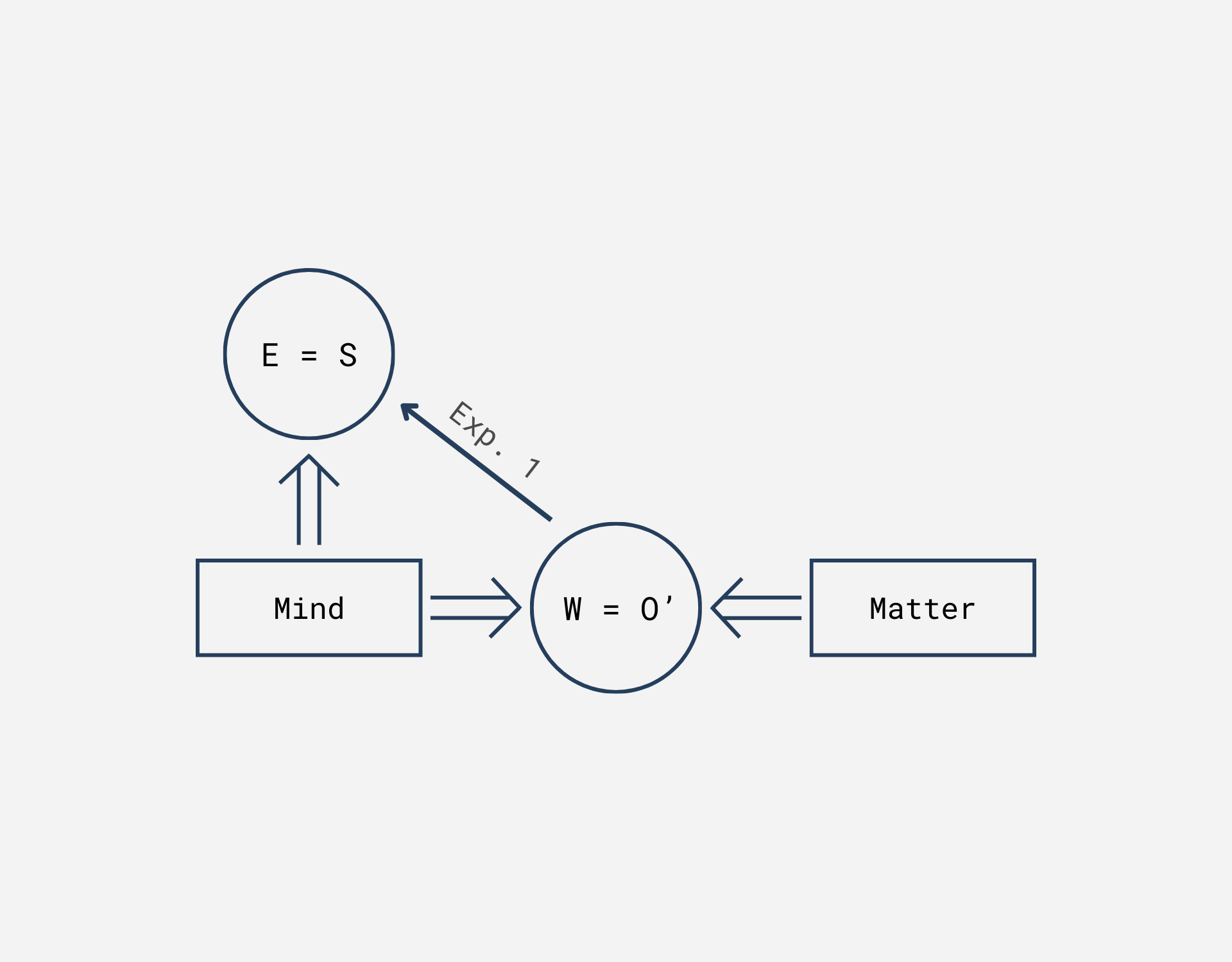

Fig 61

Husserl's epoché. When we conduct Experiment 1, our attention shifts from the Natural Attitude, N, to the way our world is given in experience.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #021

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

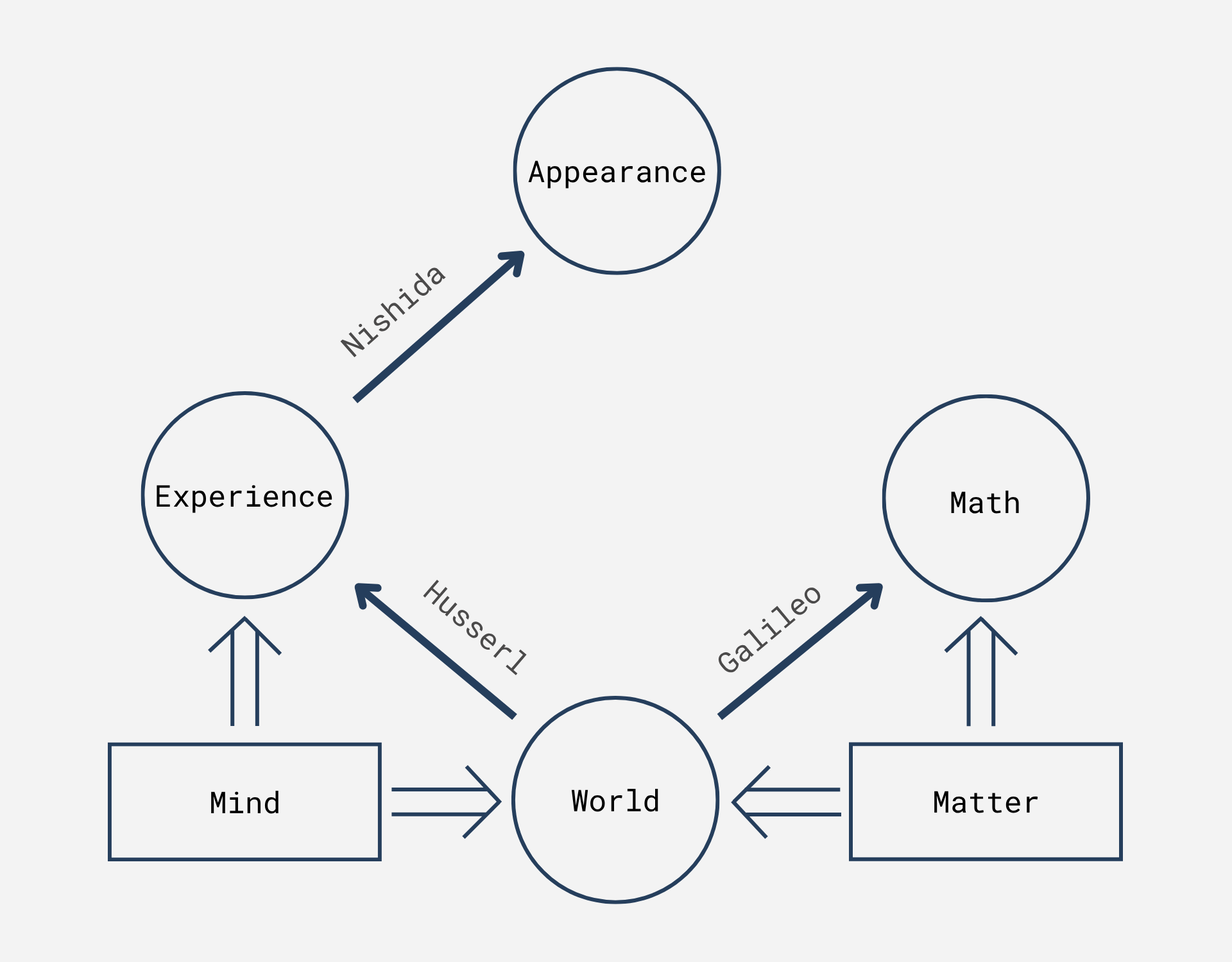

Fig 63

We have added Experiment 2, labeled as "Exp. 2," to Fig. 61. The outcome, "Appearance," has found a neutral place between Mind and Matter, two steps up from the "Material World," disclosed by the Natural Attitude.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #021

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 64

Finally we have completed the translation from ontology to epistemology, where the material world W is now seen as a representation O': W = O'.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #021

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 65

Here a different labeling is applied to Fig. 61, in order to make contact between this ontological figure and the epistemological figures in Part 3, featuring S ⊃ O' ⊃ S'.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #022

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

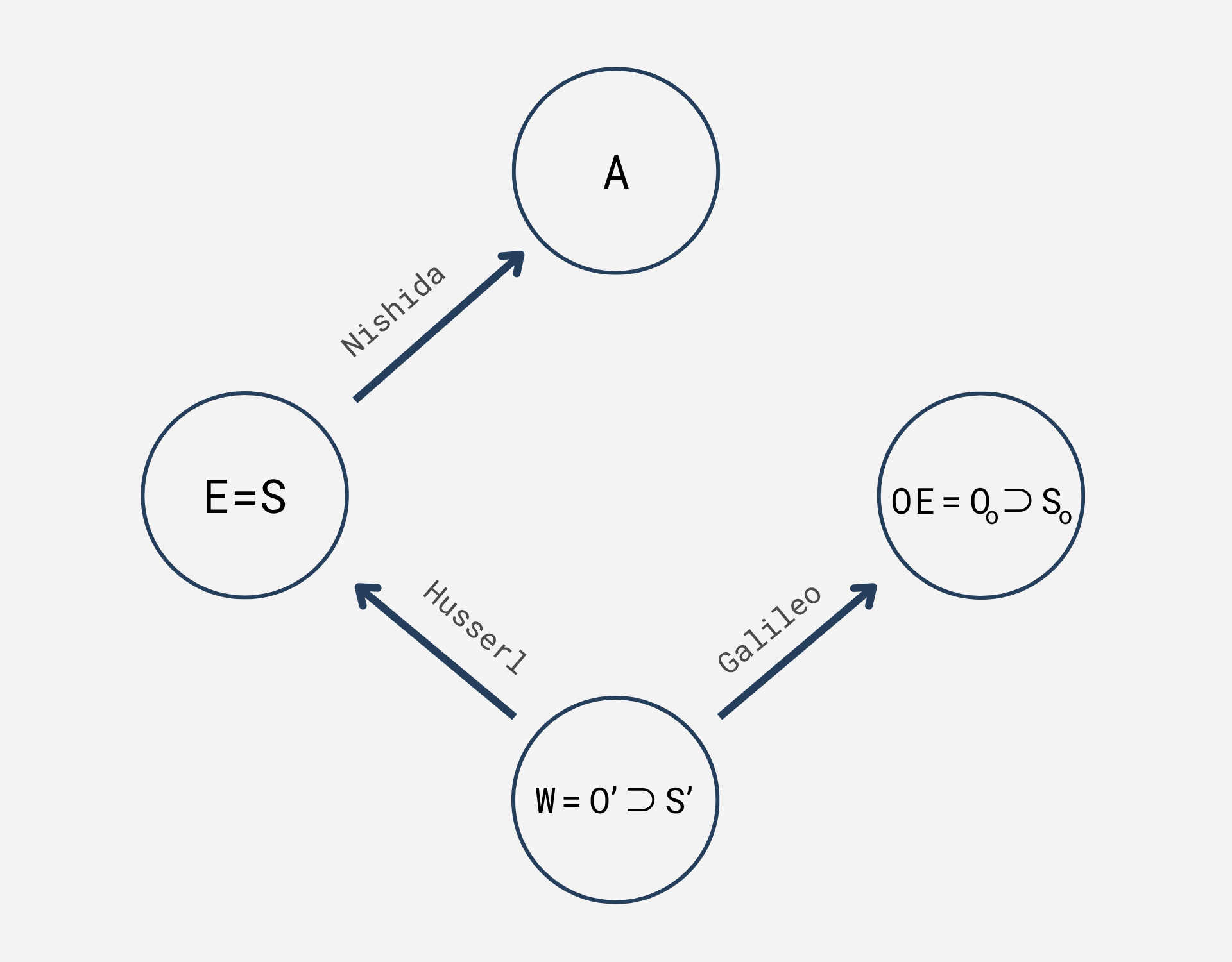

Fig 66

Option 1. This is our first attempt to translate the ontological box "matter" in Fig. 65 into an epistemological circle OE=Oo⊃So, where OE stands for viewing the world as objectified experience. In contrast, in the middle circle we view the world as an experience of a representation in our mind, W=O'⊃S'. The experience E in the upper left corner is our mind S.

Fig 67

Option 2, our second attempt to translate the ontological box "matter" in Fig. 65 into an epistemological circle OE=Oo⊃So, where OE stands for viewing the world as objectified experience. Unlike what we did in Fig. 66, we now move this circle to a level below the original place of the "matter" box.

Fig 68

Option 3, our third attempt to translate the ontological box "matter" in Fig. 65 into an epistemological circle OE=Oo⊃So. This time we move this circle to a level above the original place of the "matter" box, on a par with Husserl's "E = S" circle.

Fig 69

Here we find a symmetry between Husserl's epoché, revealing a world seen in the light of the experience of a transcendental subject, and what we could call Galileo's epoché, revealing a world seen as mathematical objects which he considered to be existing in the thoughts of God, transcendental objects in some way.

Fig 70

The three representative names of Husserl, Galileo, and Nishida are used in this diagram to indicate three different approaches to mapping an *ontology* onto the nature of reality. Galileo described a transcendental realm of mathematics as the backbone of reality on the matter side. Husserl presented a similarly transcendental realm on the mind side (the term transcendental is discussed in the next section, below). Nishida made an early step towards a synthesis of both.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

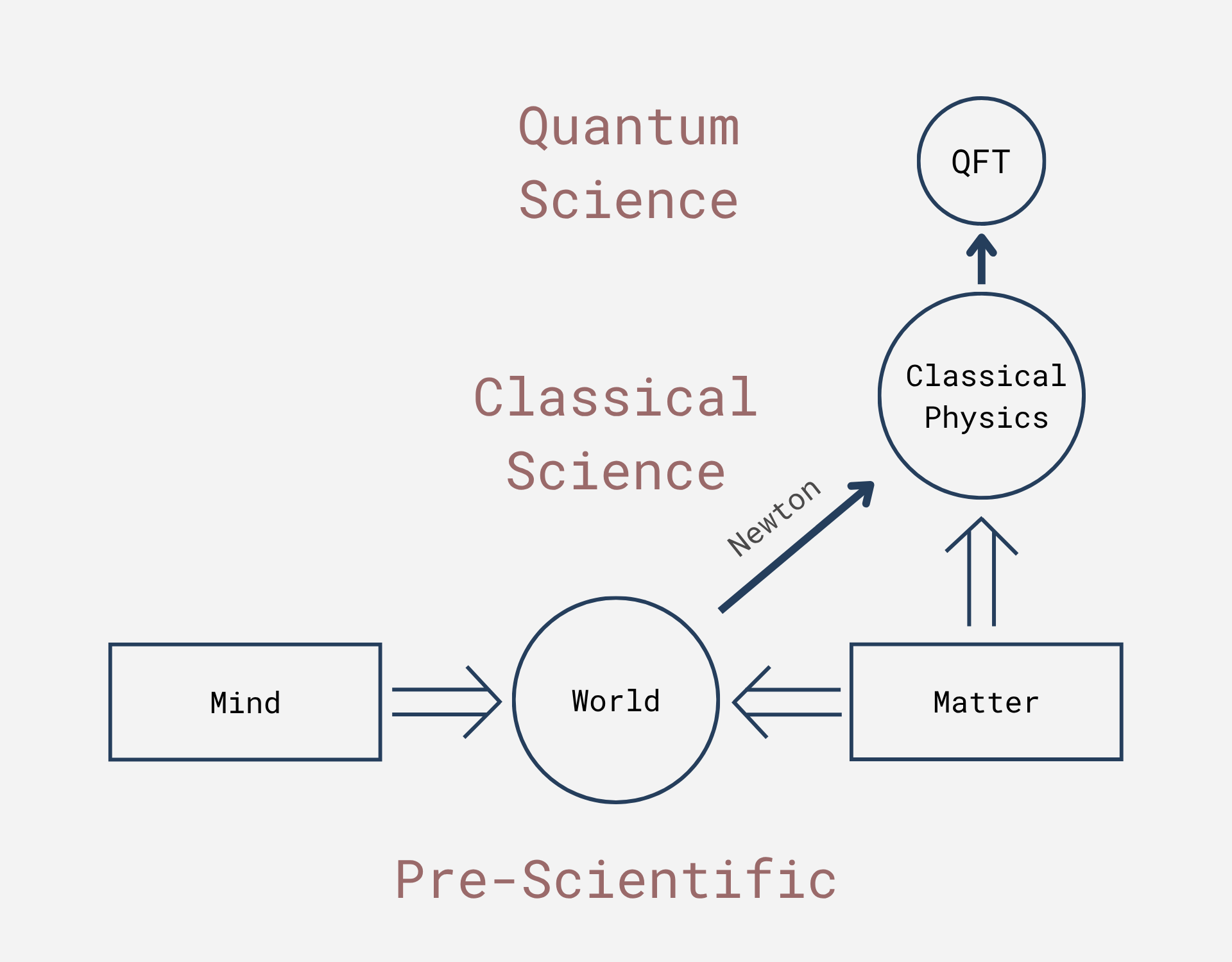

Fig 72

The matter side of Fig. 70, with "Galileo" replaced with "Newton," and "math" replaced with "physics." In addition, in red, the lowest row is characterized as "pre-scientific," while the next row above is considered to be the first "scientific" layer in this ontological diagram.

Fig 73

Like Fig. 72, but with the simple category "physics" replaced by two categories, pre-quantum "classical physics," holding sway until 1925, and "post-classical physics," here labeled as "quantum physics," from then on.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

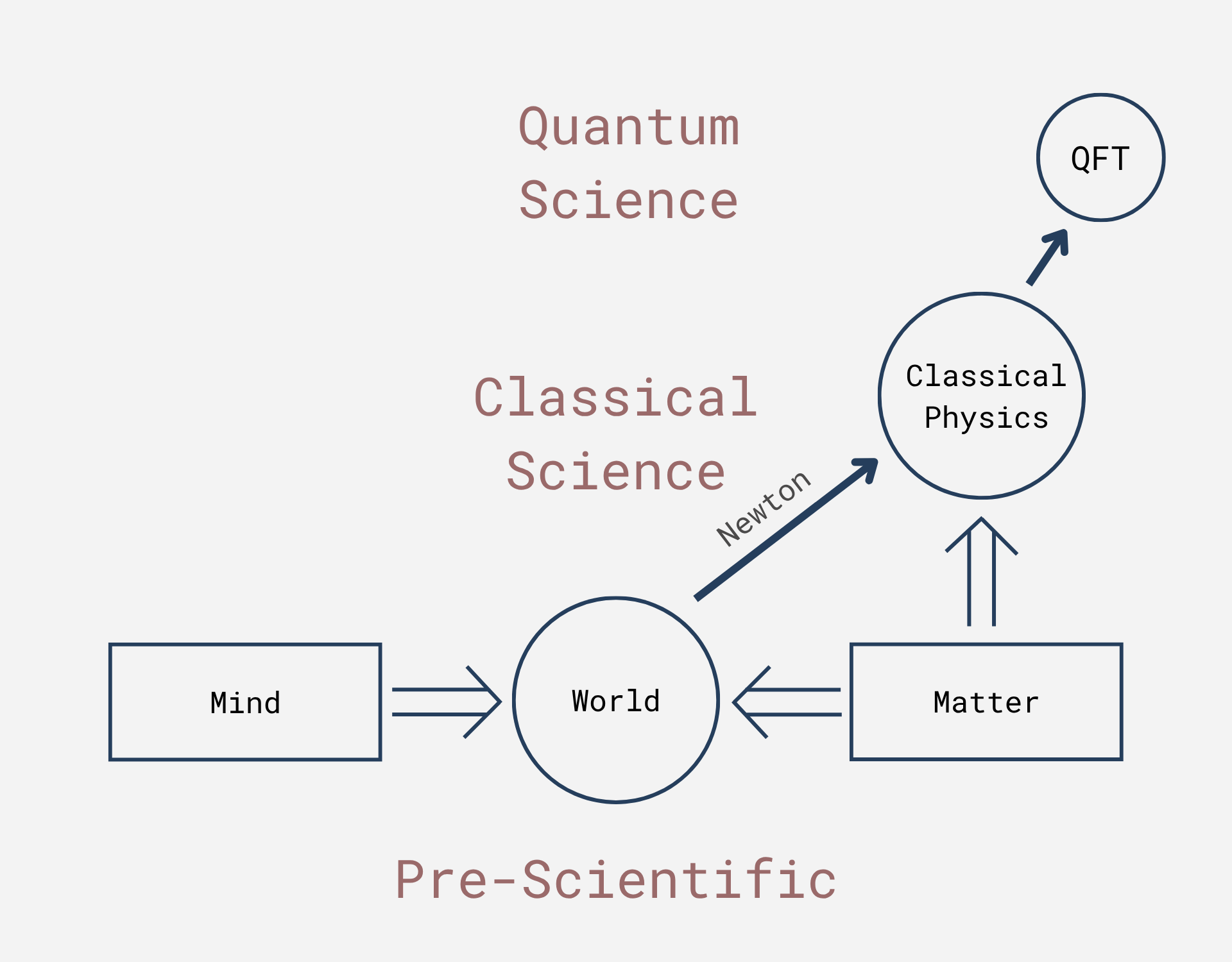

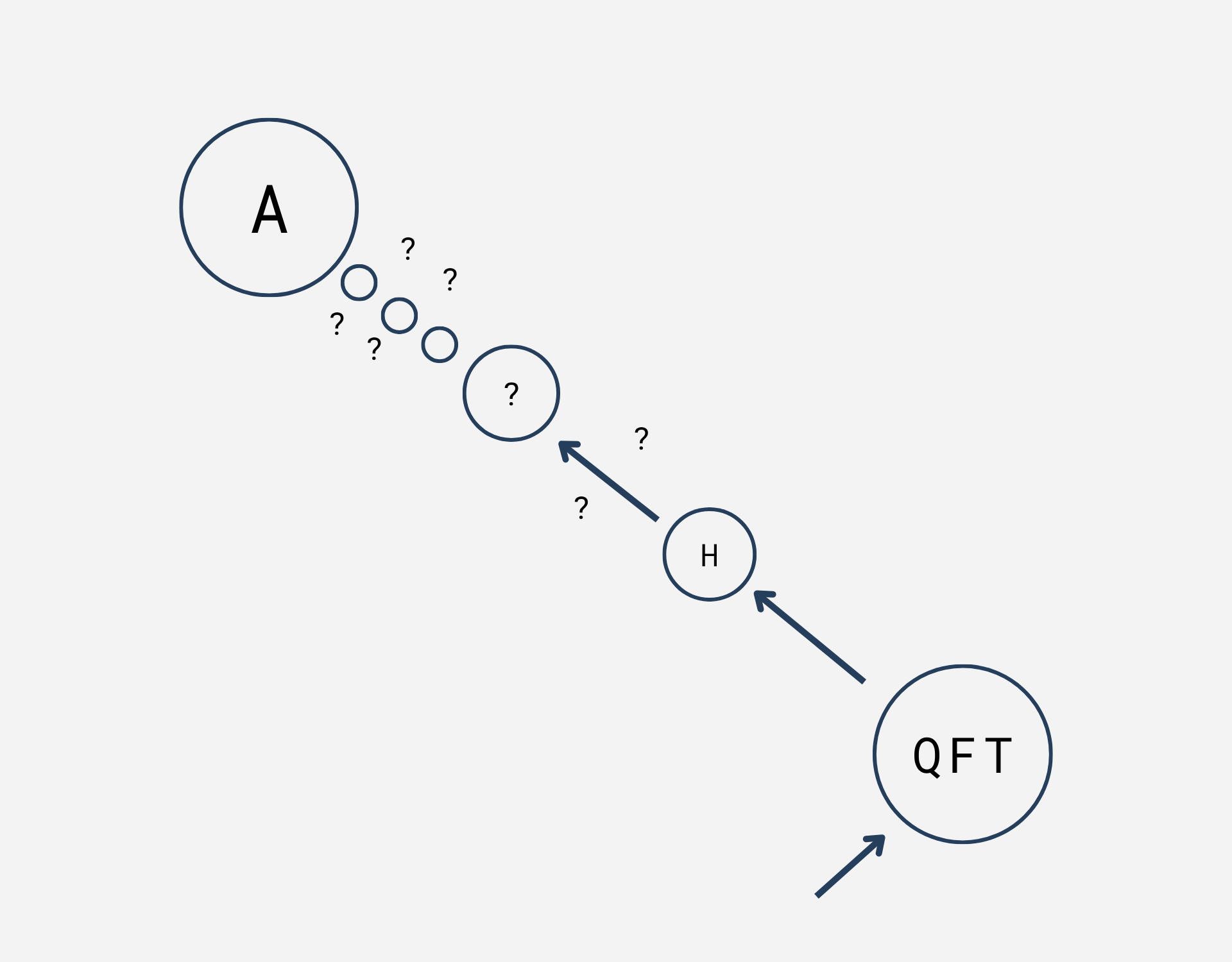

Fig 74

An alternative to Fig. 73, with QFT moved further to the right, thus making it horizontally more removed from the natural attitude, labeled "World."

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 75

Yet another alternative to Fig. 73, this time with QFT moved further to the left, to indicate the effect of the measurement problem, involving the mind, which is absent in classical physics. In the same figure, again, we have three ways to proceed when guessing the next main step of progress in fundamental physics, indicated by the three question marks.

Fig 76

This diagram illustrates a possible progression in future theories of fundamental physics, if the working hypothesis of a future matter/mind unification turns out to be correct.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 77

A refinement of the position of Nishida's contributions toward a possible ultimate nondualistic subject/object unification, by adding a little circle with the letters "PE" which stand for his expression "Pure Experience". For simplicity, I have previously used his name for the arrow from E for experience to A for appearance. But in a more close-up treatment, it seems more appropriate to line his contribution up with that of quantum physics, in moving further to the center, but not yet vertically above the starting point of the "World," leading to a diagram more akin to Fig. 76.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 78

Putting together all the pieces of the previous diagrams in the current FEST Log entry, we arrive at Fig. 78.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 79

This diagram is a simplification of the previous one, by leaving out the anticipated future progress at both sides of the "World" starting point. The two rows of circles are replaced by "!" at the left and "?" at the right. For the reasons for that move, as well as the red additions, see below.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 80

The first diagram that we encounter when descending from the level of the "World" rectangle is scientism, a caricature of actual natural science, sounding similar when presented in popular terms, but missing the actual working ingredient of science.

Figure appears in the FEST Substack Entry #023

Jump on this page to: Table of Figures for Each Part • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4

Fig 82

The double diamond diagram. Nihilism is presented here as the counterpart of the subject/object nondualism at the top. In line with the "-isms" introduced in the previous figure, nihilism would be an utterly wrong interpretation of terms like "emptiness" in Buddhism as well as similar terms in other contemplative traditions.